Piotr Faryna ピョートル・ファリナ

3. Decorative motifs

Japanese Aesthetics

The concept of aesthetics relates to the categories of beauty and art. Beauty is inherent and is associated with the notion of perfection, although this perfection can be understood in many different ways. There is no universal definition of art. It may be helpful to state that art involves the creation of a work characterized by uniqueness, originality, and inventiveness, which are the results of creative work.

Aesthetics develop tools, patterns, and criteria through which something can be judged as beautiful or ugly. It encompasses knowledge derived from reflection and experience, expressing views about art or reality in general. The culture developed by particular communities and groups produces a set of aesthetic rules, and this set is influenced by many factors including historical, religious, ideological, and social conditions.

The main goal of aesthetics is to perceive reality in terms of its attractiveness, as it answers the question of why certain phenomena/entities/objects/works are beautiful to the observer and others are not. Of course, the perception of beauty may be decided by a completely individual view, but generally, people within a given cultural circle follow commonly accepted aesthetic categories.

Far Eastern aesthetics, particularly Japanese, differ significantly from the aesthetics of Western societies. Generally speaking, in the West, beauty has an absolute dimension, is clear, distinct, highlighted, and eternal (in the sense of classical and predominant tendencies considering different modern and contemporary art trends). In Japan, beauty is individualized, concealed, misty, ephemeral, transient, passing, mysterious. The differences in the representations of objects are apparent at first glance. For example, in the West, humans were depicted naked, meticulously realistically, and pompously, while in Japan, faces were portrayed symbolically, and the body was mostly covered and usually placed in some context. Similarly, the differences are evident, for example, in landscape representations. The rules of perspective, form, and motifs also differ according to aesthetic principles.

Japanese Aesthetics: A Complex Tapestry

These are very general statements because, in the history of Japanese culture, depending on the period, there have been currents and trends that differ from this stereotypical description. Beata Kubiak Ho-Chi writes: "Japanese aesthetics, like Western aesthetics, is not a monolith, does not form a compact system. Created by humans and defining their relations through the concept of Beauty, it is as changeable as humans themselves and the reality in which they live and create" (36).

However, it is undoubtedly possible to describe a number of universal categories for Japanese aesthetics, which are commonly cited and accepted in reference to Japanese art.

Fortunately, these issues have a fairly extensive bibliography, also developed by Japanologists in Polish. Some notable works include "Culture of Japan" by Jolanta Tubielewicz, "History of Japanese Culture" by Ewa Pałasz-Rutkowska, "On the Art of Japan" by Zofia Alberowa, "Art of Japan" by Wiesław Kotański, and publications by Agnieszka Żuławska-Umeda, Przemysław Trzeciak, among others.

But above all, the source of specialized and very rich knowledge in this area is the triptych "Japanese Aesthetics" edited by Krystyna Wilkoszewska and "Aesthetics and Japanese Art" by Beata Kubiak Ho-Chi.

In principle, entire chapters of these publications should be transferred here, which would expand the article to the size of a book, and besides, I doubt the authors would be pleased with such extensive quotations. Therefore, I will limit myself to only presenting the cardinal principles of Japanese aesthetics in a keyword manner, referring interested readers to the original sources.

Japan, at least in ancient times, was not a particularly hospitable or comfortable place to live. A mountainous country, mostly made up of unusable land, located on islands that hinder communication, and prone to extreme natural phenomena such as earthquakes and tsunamis. Wiesław Kotański writes, "The Japanese, having no escape from such living conditions, ultimately came to love them and it is rare to find a nation so attached to its homeland as the inhabitants of Honshu, Kyushu, Shikoku, and other regions. Centuries of persistent struggle against adversity have cultivated many valuable character traits in this nation, such as thrift, caution, practicality, adaptability, a communal sense, accompanied by a certain dose of fatalism" (12). All of this meant that nature remained at the center of human concern. "The West has always tended to view the world by focusing on the human being (...), who 'stood in opposition to nature and tried to subjugate it to his own needs'" (36). In Japan, however, the human is an integral part of nature and not necessarily the most important part (which is evident among other things from the principles of the Japanese religion Shinto). Nature sets the standards of beauty and represents the supreme aesthetic category.

Undoubtedly, the way the ancient Japanese perceived the world was greatly influenced by philosophical and religious currents imported from the continent, specifically from China via Korea. These were deeply connected with the religion of Buddhism (particularly Zen Buddhism) and the principles of Confucianism, though they interestingly assimilated with earlier, indigenous views, creating a syncretic approach that mixed foreign influences with local Shinto.

Without delving into detailed considerations, it is worth listing only the most important features of Japanese aesthetics, commonly considered the most typical and enduring, despite the passing fashions of some historical periods for different approaches. The selected categories are listed here based on descriptions by Beata Kubiak Ho-Chi and Krystyna Wilkoszewska.

image generated by Chat GPT4 Dall-e for the prompt "Japanese melancholy" :-)

Aware (mono-no-aware)

Likely derived from the exclamation "Ahare," analogous to our "Ah...," reflecting melancholy, sadness, "tinted with the awareness of passing (...) and a sense of impermanence." It encompasses emotions, harmony, pathos, and elegance.

Yūgen

"The beauty of a secret depth" intuitively felt, containing simplicity, tranquility, charm, and sublimity. "The emotional state of a subject evoked by what is deeply hidden in nature and only suggested in its phenomena (...) The condition of beauty is not its perpetuation but rather the suggestion of its fragility and transience." Yūgen defines the unexplainable, deep feelings and the indescribable mystery.

Wabi, Sabi

Wabi and sabi are interconnected. Wabi is "the beauty of noble poverty." It signifies the serene, austere, pure beauty emanating from the depths of simple objects marked by the passage of time, even destroyed. Sabi is coolness, solitude, imperfection, patina. This aspect of Japanese aesthetics is perhaps the most well-known and recognized in the West as typical of Japanese art.

Shibui

A concept associated with ideas of incompleteness and understatement, accompanied by certainty, tranquility, and calmness as a result of consciously applying ascetic patterns of restraint and simplicity.

Iki

A modern category from the late Edo period. It includes an erotic, sensual charm, chic, flirtatious nature, and coquetry, energy, and temperament. Iki is a conglomerate of many principles of Japanese aesthetics, sometimes even contradictory, and contains both mystery, elegance, simplicity, as well as pride, arrogance, elements of bushido (warrior ideals), nonchalance, and renunciation.

Aesthetics of Form

The most distinctive features directly related to form in art were also tied to aesthetic criteria. Particularly important for the creator were:

Openness to external influences, yet creatively developed on the principle of "the student surpassing the master."

Simplicity, modesty, and economy of means of expression—an example can be seen in the Japanese lacquer technique called "black on black," which involves very subtle imagery using just one color. Essentially, the artist utilizes only what nature and experience provide, including the materials used. Simplicity "was not enforced by the simplicity of a person who could afford no more, but by the rejection of easily attainable luxury." In Japanese lacquer art, especially during the Edo period, this principle applied only to certain objects. Richly decorated objects were a sign of prestige and wealth (such as inro, which also functioned as a type of jewelry), hence the ideals of wabi/sabi were often deliberately discarded.

Fragmentation, incompleteness—in Japanese art, there is a principle of suggesting the whole through fragments. For example, an artist might use just a few brush strokes to suggest the shape of a mountain or the motion of water. Instead of depicting the entire tree, only a branch or even part of a branch is shown, yet the viewer clearly understands that the tree is an essential part of the narrative, although it is not visible in the painting.

"Empty" space—an extremely important plastic concept, assuming the participation of the viewer and the interactive effect of the image. The creator leaves free space for interpretation, allowing for contemplation and the filling in of missing parts by the observer's imagination. Sometimes in a painting, the vast majority of the surface has nothing, only in some compositionally derived place does an element appear, the development of which is left to the recipient. This is particularly important in Zen philosophy and is also related to the categories of yugen and shibui. Such a concept of "empty" space is as important as the elements that fill the space.

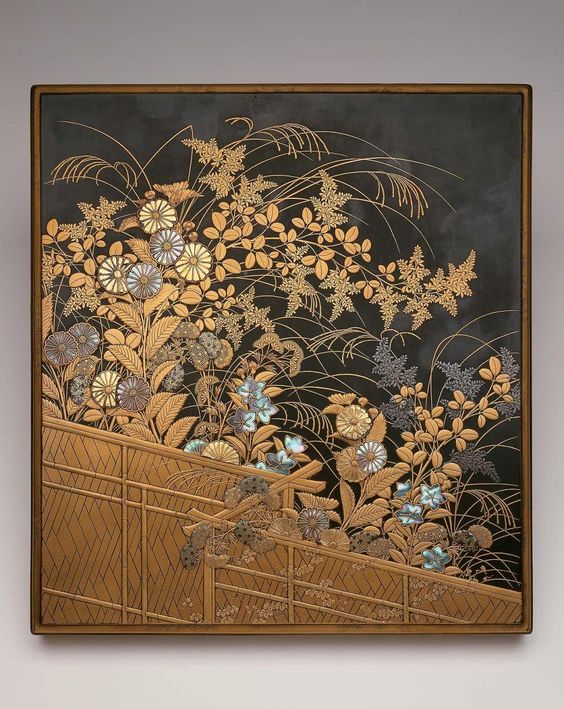

Asymmetry—one of the key elements in Japanese art and aesthetics, reflecting a deeply rooted value of harmony, naturalness, and subtlety. In contrast to Western concepts striving for perfect balance and even distribution of elements, asymmetry in Japanese art emphasizes natural beauty, refinement, and dynamics. Asymmetry involved, among other things, developing a motif along diagonals from one corner to the opposite. Often, the decoration was continued on adjacent surfaces, moving from the top surface to the side walls.

Previously mentioned characteristics, as mentioned earlier, were rejected in certain periods of Japanese art history for various reasons. Emphasis was then placed on the lavishness of decoration, the excess of form over content, banal, realistic motifs, and simple, if not vulgar ideas, all of which contradicted the aesthetic categories listed above. In my opinion, this fact does not contradict the general view of Japanese aesthetics, which is based on pillars deeply rooted in court culture, Zen, nature, Shinto elements, and the traditions of yugen and wabi/sabi.

"The continuous mixing and gradual changes of religions and ethical concepts make it sometimes nearly impossible to precisely determine the origin of certain customs or representations. On the other hand, it must be assumed that the craftsman often had no idea of the long-forgotten symbolic and ethnic origins of his works and used art simply for its aesthetic values. (...) A good example of symbolic and abstract thinking is the representation of the quail (uzura), which symbolizes: 1) the spirit of fighting 2) poverty 3) autumn 4) divinity and 5) Fukakusa – a suburb of Kyoto. The meaning of these symbolic allusions is different in each case. According to Japanese custom, the quail is a fighting bird and represents the spirit of fighting. However, the Japanese observation of nature notes the ragged appearance of the bird - hence its reference to poverty. The quail, like other birds, is also associated with millet, which relates to autumn. Mythology says that the quail transformed into a pheasant, then into the revered ho-o, or phoenix – hence the symbolism of divinity. Finally, the quail dwells in the grass, which is related to Fukakusa (fuka means hatching, and kusa means grass). (...) Sometimes symbolism can arise from the fact that a concept has multiple meanings" (7).

Anyway, in Japanese art, different meanings of words are often deliberately utilized. For example, a famous haiku by the great poet Bashō (as cited by Donald Keene in "Japanese Aesthetics," edited by K. Wilkoszewska) about a crow goes:

kareeda ni

karasu no tomarikeri

aki no kure

which can be translated as:

On a dry branch

A crow has settled

Twilight in autumn

The last line "twilight in autumn" can also be understood in Japanese as "the twilight of autumn," thus the audience may have completely different feelings, as early autumn is full of colors, warmth, and joy, whereas late autumn is more about shades of gray, cold, and sadness. Interestingly, Bashō, possibly using the above-mentioned categories of the aesthetics of form, intentionally leaves the interpretation to the reader and specifically indicates that both meanings were intended.

Literature, particularly poetry, possesses a much richer arsenal of expressive means than decorative lacquer art, yet even in this art, in the works of masters, we find a lot of symbolism, references to tradition, mood, and the perception of the audience.

In representational art, and particularly in Japanese lacquer art, creators utilized a wide range of motifs related to history, symbolism, mysticism, tradition, nature, and phenomena of the surrounding world. "The subject was an allusion, and its interpretation depended on the intelligence, education, and sensitivity of the viewer" (2).

Among the various objects adorned using lacquer techniques, there are, of course, those that do not possess artistic qualities and do not relate to any symbolism or deeper meaning, presenting only decorative elements. However, even with basic knowledge of Japanese culture, it is quite easy to distinguish them.

In a simplified manner, these motifs can be presented by classifying them into the categories specified below. The following compilation is a summary of recurring elements found in the bibliography mentioned by me on the main page www.lakajaponska.pl, information from the internet (for example, the blog about Japan https://matsuki.pl – a number of citations refer to this address) and my own observations. There is a lot of this data, so I do not cite specific sources as it would introduce considerable chaos and reduce the readability of the description

Motifs

GODS and RELIGIONS

According to the oldest sources of written history/mythology of Japan (Kojiki - Records of Ancient Matters and Nihonshoki - Chronicles of Japan, compiled in the early 8th century AD), among the pantheon of gods associated with Shinto religion are such figures as Izanagi (male principle), Izanami (female principle), and their most important "creations": the goddess Amaterasu and her brother Susano-o. From subsequent generations emerges another significant figure: Ninigi, who holds the gifts from the gods in the form of a mirror, sword, and jewels, which will become regalia for future emperors. According to legend, Ninigi's grandson, Jimmu Tenno, was elevated to the throne as the first emperor (of Japan?, or at least of an unspecified part of the archipelagic territory) and ruled approximately between the 7th and 6th centuries BC.

In addition to these mythological figures, the Shinto religion also includes a multitude of countless kami - supernatural spirits and various gods. Indeed, the whole concept of Shinto assumes that a deity can take any form or incarnate in any object, and thus due respect can be paid to the sun, a river, an animal, a specific tree, an ancestor, or even stones... In lacquer art, direct references to Shinto religion are rare, unless we consider natural motifs from this perspective.

On the other hand, Buddhism, introduced from the continent in the 6th century AD, achieved immense success in Japan. Among the most important beings in Buddhism (bodhisattvas) is the goddess Kannon. This figure has inspired many lacquered works, mainly sculptural in wood covered with lacquer or crafted in the ancient kanshitsu lacquer technique. Continental philosophical and religious currents such as Taoism and Confucianism have left a strong imprint on aesthetic criteria and decorative motifs. Figures, symbols, and concepts related to Buddhism, especially Zen Buddhism, are very frequently used in Japanese lacquer art. References to the concept of yin and yang, characteristic parables, symbols, and related beliefs, ideas, and legends based on Chinese patterns are commonly found.

- The Seven Gods of Fortune (shichi fukujin)

According to Japanese mythology, the seven gods of fortune travel on a dragon-shaped ship filled with treasures and magical items. They bring luck, wealth, and success in life to their followers. These gods are often portrayed in lacquer art. They make a delightful subject because, firstly, they are believed to bring people luck and longevity, and secondly, they are charming and bring a certain element of humor. Although called gods, they are more akin to talismans and are more associated with the family home than the temple. They are primarily portrayed individually, but also in groups. The representatives of shichi fukujin are:

Benten – the only female figure. She represents knowledge, wisdom, motherhood, education, talent, and art. Her messenger is a dragon or a white snake. She is mostly depicted sitting on a dragon, holding a musical instrument and a key in her hands. A protective deity. She aids betrayed, jealous, or lonely women. She is also the patron of gamblers, merchants, and speculators.

Bishamon – represents strength, fighting spirit, and wealth. The patron of soldiers. He is depicted in armor, holding a spear in his right hand and a model of a golden pagoda in his left. He often tramples two demons. He possesses immense wealth and bestows people with ten types of treasures and happiness. He protects from diseases and malevolent demons.

Daikoku – deity of wealth and prosperity. Daikoku’s messenger is a rat (also a symbol of wealth), and his attributes include a lucky hammer and bags full of valuables. The patron of wealth and agriculture. He is dressed in a hunter's attire and surrounded by symbols of prosperity: standing on rice bags, with a rice bag also slung over his back. In his hand, he holds a wooden hammer, which he uses to grant wishes directed at him. Images of Daikoku are often placed in kitchens, and since the kitchen gets sooty, he is sometimes depicted with a dark/dirty face.

Ebisu – deity associated with fishing and wealth. Ebisu is the patron of wealth multiplication, physical labor, and business. His messenger is a sea bream. He is depicted as a short, plump, bearded fisherman with a fishing rod or net and a fish in his hand. He is commonly venerated by shopkeepers, traders, and business owners.

Fukurokuju – god of wisdom, luck, fortune, and longevity. He has the form of a short, elderly man with an unnaturally elongated skull, signifying wisdom and long study. In one hand, he holds a staff, and in the other, a fan. His messengers are the crane or the turtle (symbols of longevity).

Hotei – a fat, jovial, careless monk, one of the most beloved gods. He is depicted as a smiling monk with a bald head, a large, exposed belly, and a sack on his back. He is akin to Santa Claus. Children often accompany him. He is the patron of good humor and family happiness.

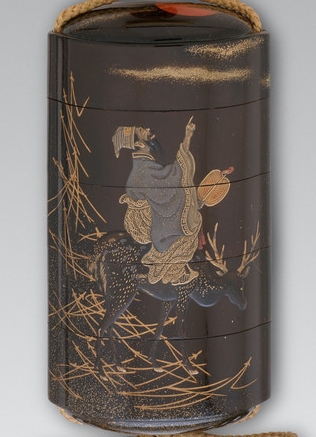

Jurojin – responsible for longevity, depicted as an old man with a long, white beard dressed like a Chinese scholar, wearing a small hat. He holds a fan and a scroll, which some believe contains the birth and death dates of people, or perhaps all the wisdom of the world, symbolizing his power as the god of longevity. His messenger is a deer.

Daruma - (the Japanese equivalent of the Indian Bodhidharma). Daruma is not a god but a very important religious figure—a Buddhist Zen priest who served in India in the 6th century AD and was a traveling missionary to China and Japan. Due to his piety, he reportedly sat and meditated non-stop for nine months without moving or speaking. As a result, his legs atrophied, and he is said to have cut off his own eyelids to avoid falling asleep (legend also says that tea bushes later grew from these eyelids). In Japanese art, he is often depicted with a rounded silhouette, lacking legs. His eyes are wide open, and his face contorted into a grimace. He is sometimes portrayed in a caricatured or symbolically simplified manner.

Sennin - Hermits who achieved immortality through meditation and asceticism (according to Taoism). There are many of them, and they often appear in lacquer art. Sennin possess magical powers, concoct the elixir of life, and dwell in caves. They are depicted in human form with large ears and long beards. The most famous is Gama Sennin, who lived with a companion in the form of a three-legged toad.

Uzume - (Ame-no-Uzume-no-Mikoto) Goddess of dawn, meditation, and mirth. She is a patron of young marriages, pregnant women, and dancers. This Shinto goddess is often depicted in a humorous or erotic manner. She has a round face with puffed cheeks and tiny lips, always smiling.

Hachiman - In Japanese mythology, he is the god of war, warriors, and archery. He is a protector of Japan, the Japanese people, and an advocate for the emperor. He is also associated with agriculture, fertility, and fishing. It was believed that Hachiman was the instigator of the "divine wind" kamikaze, which dispersed the Mongol invasion of Japan in the 13th century.

Fudo - One of the Buddhist kings-guardians, a deity of wisdom, and a patron of astrology. He has a fierce facial expression, braided hair, and two protruding fangs. Surrounded by flames of wisdom, he holds a rope to bind the guilty and a sword to ward off villains. Due to the flames, he is sometimes mistakenly considered a god of fire.

Raiden and Futen - Raiden is the god of thunder, and Futen is the god of wind. Raiden resembles a devil with goat horns, surrounded by drums arranged in a circle. He holds bones, which he strikes against the drums to create thunder. Futen also resembles a devil with protruding fangs, pointed ears, and three-clawed paws. He holds the ends of a blown-up bag, releasing wind while standing on storm clouds.

Nio - These are two temple gate guardians, typically placed on either side of the entrance to protect the sacred place from evil spirits. They are depicted as muscular figures with fierce expressions.

Oni - Oni demons represent diseases. They look like imps and are sometimes presented in a humorous manner. Often depicted in lacquer art, they have square heads with horns on the forehead, mouths that stretch from ear to ear, and menacing eyes. They are expelled from homes using spells and roasted black beans, which they fear. Hence, in depictions, they are seen hiding from a barrage of beans.

CHARACTERS and LEGENDS

Most of the figures celebrated in narratives, such as knights and heroes, were historical figures who actually existed in social life. Their deeds, often exaggerated or embellished to various degrees, did occur as derived from various descriptions and documents.

Kuge, Daimyo, and Famous Clans

Kuge refers to the highest aristocracy centered around the imperial court. Daimyo, on the other hand, were powerful lords, somewhat akin to sovereign princes, who ruled over specific territories/provinces with a considerable degree of independence, varying across historical periods. Daimyos managed entire villages and cities and had their own units of samurai at their disposal. The institution of the clan (family) was immensely important in Japan. The entire social structure was based on a feudal system where most people were "affiliated" with a clan. Famous families that played a significant role in history and became part of the country's tradition include, among others, Soga, Fujiwara, Taira (Heishi), Minamoto (Genji), Takeda, Hojo, Ashikaga, Tokugawa.

Since for several hundred years (roughly from the 10th to the 17th century AD), there was more or less frequent outbreak of armed conflicts between the clan factions, a significant portion of artwork features references to famous battles and wartime heroes. They are depicted in armor, with weapons (bows, swords, spears), a formidable demeanor, inspiring respect and admiration.

Gempei (Genpei) War

This famous military conflict took place at the end of the 12th century between two Japanese clans vying for control of the country: the ruling Taira clan and their challengers, the Minamoto clan. The name Gempei comes from the Sino-Japanese reading of the clan names: Minamoto - Gen and Taira - (P)Hei. These battles are chronicled in the epic saga Heike Monogatari. A notable figure was Minamoto Yoshitsune, one of the sons of the Minamoto clan leader. As a general, he contributed to the final defeat of the enemies and was celebrated as a hero. He was accompanied by his closest friend, the warrior-monk Benkei—a legendary figure in history. Unfortunately, due to accusations of conspiracy, he was forced to commit ritual suicide (seppuku). This tumultuous story has become a popular theme in Japanese art, though very rare in lacquer work.

Uesugi Kenshin and Takeda Shingen

These are heroes of another famous conflict between the Uesugi and Takeda clans, which took place in the mid-16th century. These battles are remembered and recorded as an exceptionally honorable war. As adversaries, Kenshin and Shingen held each other in high esteem. Shingen gifted Kenshin a highly valuable sword, illustrating his respect for his opponent. In turn, Kenshin, when his enemies ran out of salt, sent them some as a gift. These events and characters have been reflected in art.

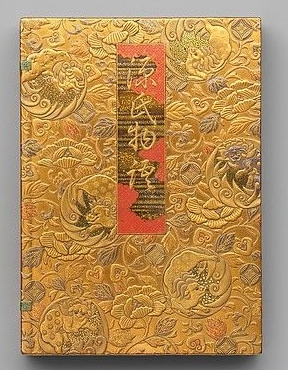

The Tale of Genji

In various works of Japanese art, themes related to "The Tale of Genji" – the most famous novel written by the court lady Murasaki Shikibu in the 11th century – often appear. The story of the beautiful Prince Hikaru and his romantic adventures has ignited the imaginations of readers for hundreds of years, and artists (mainly painters) have created numerous illustrations for this book.

47 Ronin

This extremely popular story, known worldwide through literature, theater, and film, is not commonly featured in lacquer art, to my knowledge, or is very rarely presented.

The Dream of Rosei

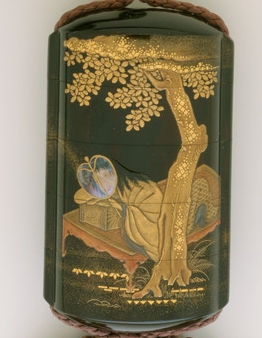

Often depicted in lacquer art is the legend of Rosei, who was an envoy on his way to meet the Chinese emperor. Along the way, he met the immortal Lu Kung, who gave him a magical pillow. When he fell asleep, he dreamed that he had achieved a high position, and then his enemy wanted to cook him in boiling water. When he awoke, he realized that the dream was related to the hot, steaming food that had been served to him. He understood the transient nature of earthly goods and the vanity of human endeavors. He is depicted lying on a pillow with a fan (the fan is made in such a way, e.g., of semi-translucent mother-of-pearl, that his face can be seen through it).

DEMONS and MONSTERS

Tengu

Mythical creatures found in Japanese folklore, Tengu are depicted as beings that combine human and avian traits and have long pointed noses. They inhabit remote mountainous areas in forests. In Buddhism, Tengu were considered malevolent demons heralding war. Over time, their image transformed into protective, though still dangerous, spirits of the mountains and forests. Tengu are associated with ascetic practices known as shugendō and are often depicted in the attire of shugendō practitioners – yamabushi. In art, Tengu are variably shown, but most commonly as something between a monstrous bird and a humanoid entity.

Yurei

Ghosts of the deceased. They typically have long straight hair, an elongated neck, emaciated white faces, and bodies that taper into nothingness, as they lack legs. Some are gentle, while others are vengeful. In folk tales, ghosts also include repulsive goblins of various shapes.

Ryu, Tatsu (Dragons)

In mythology, dragons have Chinese origins and are depicted in various forms. They are most commonly based on Chinese imagery: a camel-like head, an open mouth, prominent eyebrows, round eyes, and donkey ears. They have four short legs with claws. The body is usually coiled and elongated. They do not breathe fire.

Ho-o (Phoenix)

Has the head of a pheasant, the crest of a rooster, the neck of a turtle, the beak of a swallow, and features of a dragon and fish. It has long, narrow feathers. It perches on trees and sings melodies. The Phoenix is gentle and symbolizes happiness and longevity.

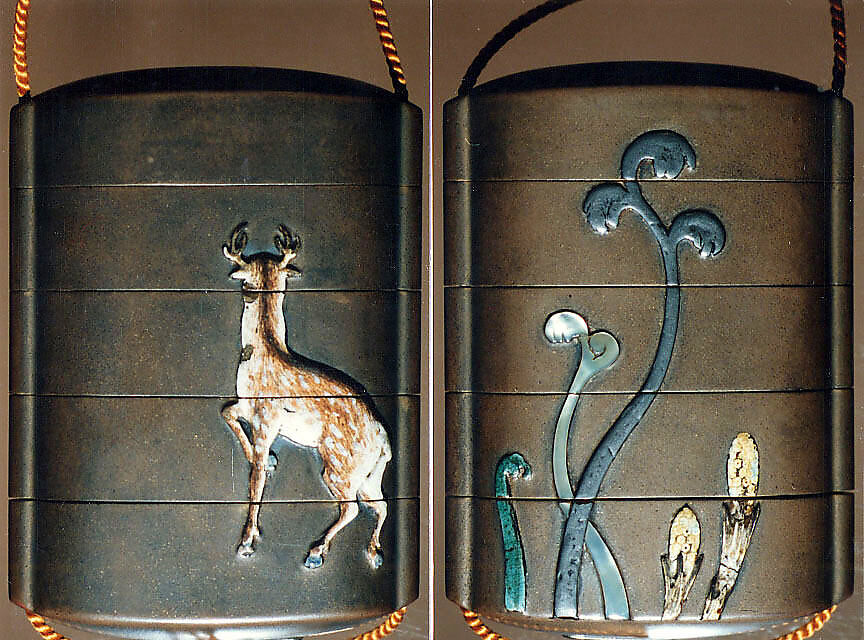

NATURE

Melvin, Betty, and Jahss report that detailed analyses indicate that 80% of the themes depicted on inro in the 18th and 19th centuries focused on nature (landscapes, fauna, and flora). As I mentioned earlier, nature was the leading decorative motif in lacquer art. The paintings included a variety of plants, land and water animals, birds, and insects. There are also frequent combinations of different animals accompanied by plants in reference to symbolism (for example, animals and plants similarly symbolizing longevity) or beautifully composing (for example, a sparrow on a bamboo branch).

VEGETATION

Flowers, grasses, and trees

Below are examples of a few of the vast number of these plants. Bamboo is a unique plant/grass. It is extremely durable and flexible. It grows very quickly and is evergreen. It is suitable for a wide range of applications. Its segmented structure has symbolic meaning suggesting certain stages of development and the fact that each subsequent stage/segment must be preceded by the previous one. "It therefore serves as a good example of life for a human or development for a child. This tree reproduces quickly, sends out new roots, so it is associated in Japan with numerous offspring and a large family." It is a symbol of fidelity, constancy, and strong character. Together with the sparrow, it signifies friendship and family.

Sakura – cherry blossom

In Japanese tradition, perhaps the most characteristic tree, or rather its flowers. The blooming cherry tree is one of the symbols of Japan and Zen Buddhism symbolism. The flowers, which last very briefly on the tree, are associated with the concepts of impermanence, transience, and loyalty through the ideals of a samurai ready to sacrifice his life for his lord. (cherry blossoms look) "Just as human life, although beautiful and captivating, is very fragile. It has long been believed that gods responsible for good crops live in cherry trees. Thus, Sakura is a symbol of abundant harvests and wealth."

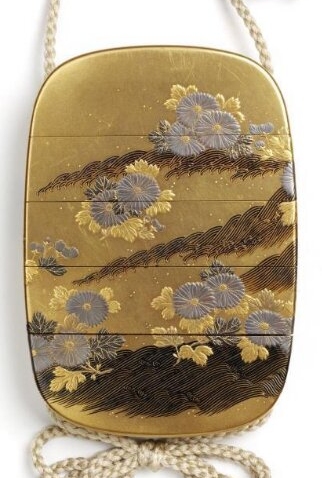

Kiku – chrysanthemum

Valued as a beautiful autumn flower. Especially popular is the 16-petaled chrysanthemum that serves as the official imperial emblem, as it resembles the rays of the sun. It symbolizes peace, nobility, and long life. It was also believed to have medicinal properties.

Hyotan – Gourd

This fruit-container, very durable, symbolizes longevity and health. It often appears in lacquer work illustrations. It contains many seeds, which are associated with children and a large family. "The shape of the gourd gives the impression that it is filled with something inside. The Japanese believed that it absorbed evil powers that could not escape outside. Thus, the gourd also served as a kind of amulet protecting against evil. (...) The dried fruit's shell becomes hard and does not allow fluids to pass through, so it was used in Japan like a thermos."

Shobu, kaikitsubata – Iris

The long flat leaves of the iris are reminiscent of a sword, symbolizing strength and victory. Sometimes their magical healing powers are mentioned. "The iris blooms in May and June, usually with intensely purple or blue flowers. In design, it often appears with symbols of water, rivers, etc. (...) Another meaning of the iris is a symbol of marital fidelity and longing for one's homeland."

Hasu – Lotus

Similar to the water lily, it is exceptionally often a motif in lacquer art. It is an emblem of Buddhism - the Buddha usually sits on the lotus flower, and since its round form is similar to the spokes of a wheel, it refers to reincarnation and symbolizes purity. "The lotus opens its blossom in the morning and closes in the afternoon to greet the sun again the next morning. For this reason, it is attributed meanings of eternity and prosperity."

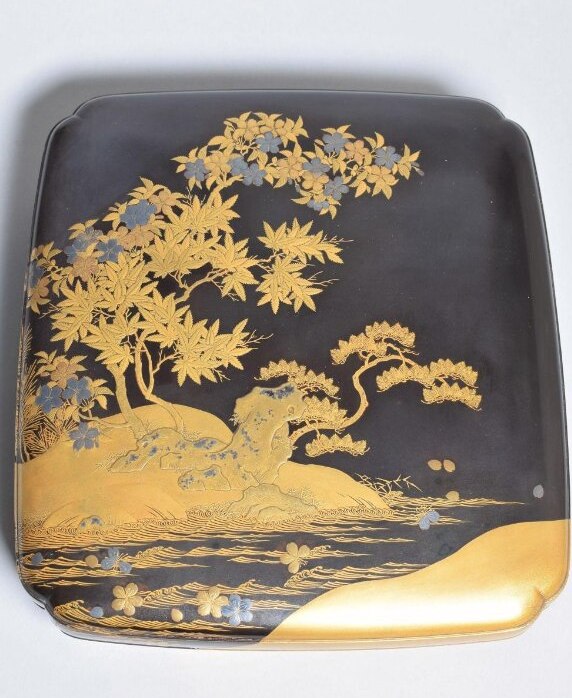

Momiji – Maple

A popular motif associated with changing emotions, as the leaves of the maple change colors and are associated with autumn. "Just as a spring carpet of sakura petals on water, so the slowly floating autumn maple leaves delight nature enthusiasts every year.

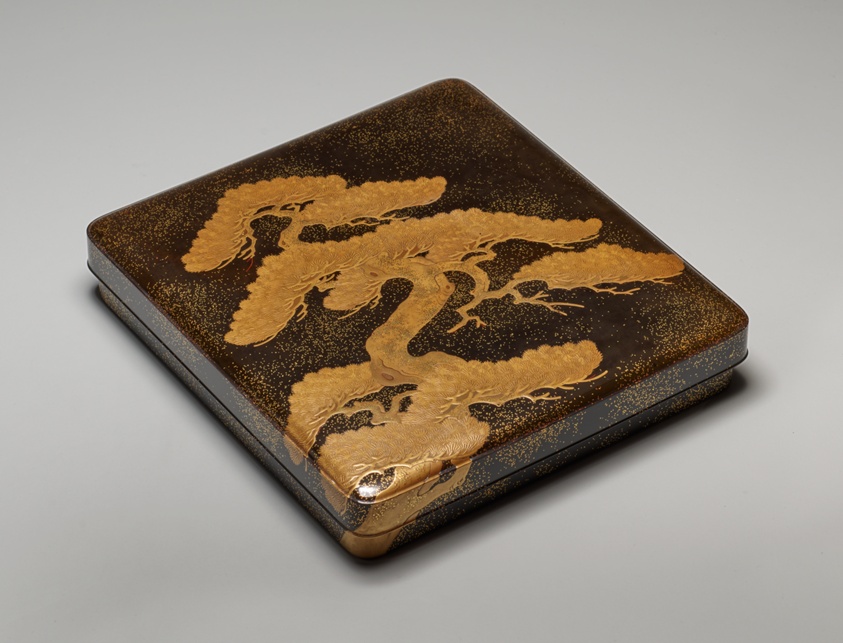

Matsu – Pine

An evergreen, weather-resistant tree. A symbol of stability and loyalty. Often depicted in landscapes. In Japanese design, pine is characterized by its umbrella-like shape but is also represented as branches with clusters of needles.

Ume – Plum

One of the most popular plants in lacquer art due to its distinctive flowers, usually presented symbolically in geometric form. It blooms the earliest, thus associated with spring and happiness. "Plums bloom first in the year, even when it is still cold. They herald the approaching spring. Plum flowers are associated with perseverance and resilience. Trees sometimes bloom when snow still lies on the branches," symbolizing endurance, strength, and beauty.

Aki kusa - Seven grasses/herbs of autumn

A commonly used motif depicting a meadow with various plants swaying in the wind. Linked to feelings of solitude and nostalgia, as well as cheerful old age. Valued for its delicate and very atmospheric impressions.

Yanagi – Willow

Its characteristic flexible branches are a symbol of prudence, flexibility, and patience, as it gently sways and yields to gusts of wind. "Among the many types of willows, the most popular in Japan is the weeping willow. It appears soft and weak, but in reality, the willow is very flexible and durable. It is believed to protect against evil and misfortune."

Fuji – Wisteria

Known for its beautiful garlands of purple flowers. A symbol of femininity, youth, and spring.

LAND ANIMALS

Inoshishi – Boar

The boar is admired for its great courage and indomitable spirit. It charges straight towards its target, never backing down. Symbolizes conquests and an unwavering attitude associated with samurais.

Neko – Cat

The cat has many symbolic meanings. It is credited with the power to bring good luck. A figurine of a cat with a raised paw not only protects property (like from mice) but also influences success in business and invites guests and customers.

Shika – Deer

The deer symbolizes faithfulness and loyalty. Often in the company of mythical characters. It has the power to extend life. In Nara, sika deer roam freely through the streets, making them a tourist attraction. The deer is also associated with autumn.

Inu – Dog

The dog has always been a friend and defender of humans. It protects its master from demons, fire, and theft. Since dogs typically have numerous offspring, they symbolize safe childbirth and healthy growing children.

Kitsune – Fox

There are three types of foxes: the field fox that steals from the farmer, the good Inari fox, and the bad, demonic, and possessed fox. It possesses wisdom, predicts the future, and delves into mysteries. It can transform into other beings and has magical powers. Some foxes are malicious and can cause possession, but others are benevolently benevolent. In art, the fox often appears in female attire.

Usagi – Rabbit

It is believed to live a very long time and is associated with the moon. "Rabbits are very popular in Japan, credited with the ability to match couples and find suitable partners. As messengers of the gods, they take care of marriage. The rabbit's hops symbolize energetic progression through life's path and overcoming all difficulties. The rabbit is also a symbol of entrepreneurs and businessmen. Especially the image of a rabbit facing forward (maemuki) symbolizes optimistic advancement. Rabbits move only forward, never turning back. Their short front legs allow them to quickly climb slopes."

Uma – Horse

A symbol of high social origin and wealth. Associated with the military, it symbolizes strength, endurance, and vitality.

Karashishi and Tora – Lion and Tiger

Often used as motifs, though these species are not naturally found in Japan. They symbolize courage and extraordinary strength. Even the wind, as the strongest element of nature, cannot defeat the lion.

Saru – Monkey

The monkey has playful, funny, and humorous traits, often depicted as mimicking human postures. "The word for monkey in Japanese is saru, which is a homonym for the verb meaning to pass or end. Thus, in Japan, the monkey is associated with protection from misfortunes and disasters, symbolizing that all failures will quickly end and fade into oblivion."

Ushi – Ox

The ox has a gentle disposition, is slow but strong and loyal. It assists in plowing and is therefore associated with spring. It is depicted as being ridden by a boy playing a flute, which represents peace of mind and safety.

Nezumi – Rat

It is one of the favored animals and considered a symbol of luck and wealth. Its silhouette, due to its long tail, is often placed across various surfaces of lacquerware, moving from the top panels to the sides and back.

Hebi – Snake

The snake has inspired artists since ancient times. Depictions of the snake are usually fantastical, similar to a dragon. Generally, it is a symbol of deceit, cunning, and jealousy

WATER ANIMALS

Koi – Carp

The carp, overcoming the current of the river and swimming upstream, symbolizes strength and perseverance in pursuit of a goal. "The symbol of the carp harbors wishes for success and prosperity in life." Often found in lacquer art, there are even special guides on how to paint the scales and shape of the fish in various configurations.

Kani – Crab

In Japan, the crab is associated with combativeness. It has a hard shell and a pair of very strong pincers. Crabs, moving swiftly and efficiently sideways, symbolize readiness to fight, strength, and perseverance.

Ebi – Lobster

Due to its bent shape, the lobster is considered a very old creature and another symbol of longevity. Frequently a motif in lacquer art, especially depicted in high relief and finished with red lacquer (as lobsters turn a deep red when cooked).

Tako – Octopus and Squid

With their many tentacles, they symbolize numerous offspring and happiness. Sometimes depicted in a comical or erotic context.

Tai – Sea Bream

Because it is "humpbacked," similar to a lobster, it is associated with old age and thus is a symbol of longevity. Also, like the carp, it swims upstream, signifying stubbornness and overcoming adversity.

Gama – Toad

It is believed that toads can escape captivity even under the most unfavorable conditions. They possess magical powers and knowledge about roots and herbs. They are constant companions of Gama Sennin.

Kame – Turtle

There are two types of turtle representations. The first is a realistic turtle, and the second is a long-tailed turtle, where the tail, because of an attached moss-fungus, resembles a straw raincoat. The distinctive shell pattern is very characteristic in decorations.

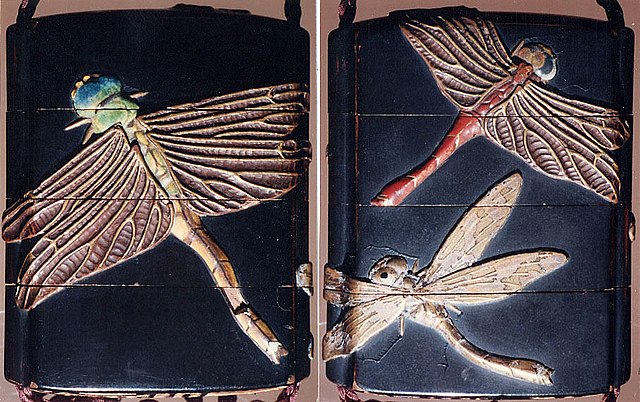

INSECTS

Interestingly, the Japanese did not regard insects with disgust, but rather admired them and even kept them as household pets, listening to the sounds they made (e.g., cicadas or field crickets). Insects, due to their small size, are excellently suited for decorating small objects. Some of them, presented on lacquered items, include:

Ari – Ant

It represents industriousness and thrift. In lacquered objects, it is depicted, for example, in the technique of metal inlay.

Cho – Butterfly

The natural beauty, grace, and delicacy of the butterfly made it a popular motif. Symbolically, it represented summer and was associated with young women. "The butterfly, transforming from a larva into a beautiful adult, symbolizes immortality in Japan. For this reason, it was also favored by warriors."

Tombo – Dragonfly

Though it appears delicate, it symbolizes courage and victory. "It seems to fly a bit chaotically, but always straight ahead, never turning back. Because its eyes are large relative to its body, it is considered to have excellent vision. Dragonflies were a favorite symbol among Japanese warriors."

Hotaru – Firefly

Associated with summer and light. Linked to delicacy and poetry.

Kumo – Spider

Associated with both good and evil, industriousness, and magical craftsmanship. The intricate web woven by the spider is one of the favorite motifs, possessing significant decorative value.

BIRDS

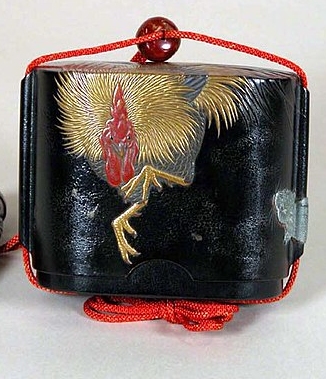

Tori – Rooster

A strongly masculine element. It fights its enemies fearlessly. It has a proud stance and beautiful plumage, symbolizing a fighting spirit. Its beauty and graceful long tail are well suited for depiction by lacquer artists. The rooster on a drum symbolizes peace and contentment (according to legend, the rooster occupied the place on the emperor's drum, which was meant to call warriors to battle, but there was no need, so the drum was merely a place for the rooster to stay and rest).

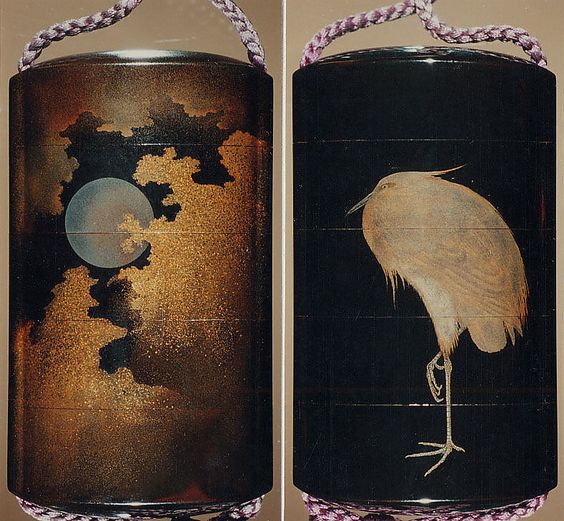

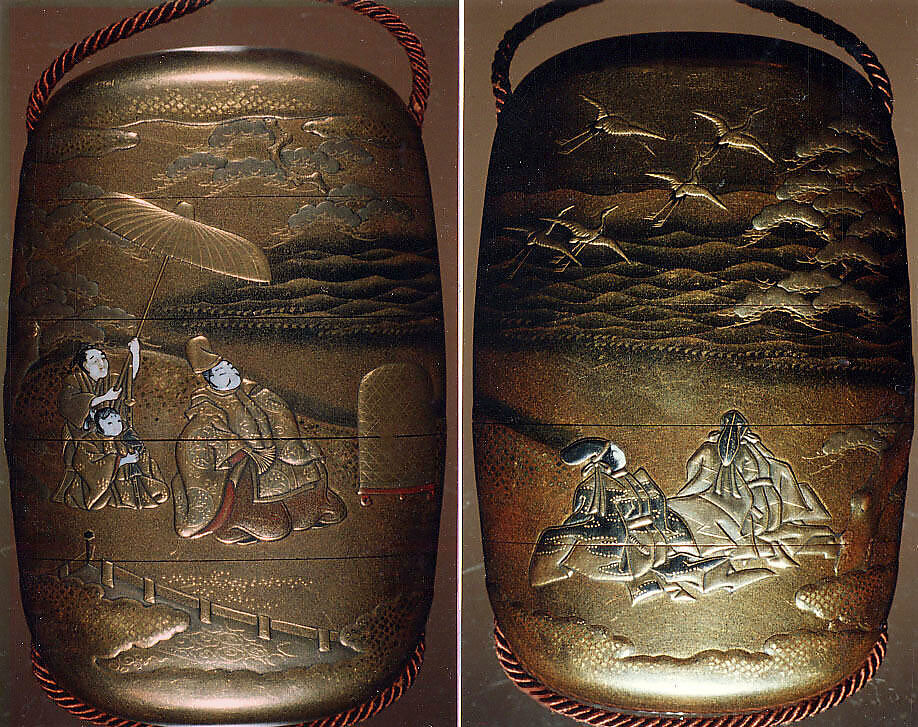

Tsuru – Crane

The crane symbolizes longevity as it lives relatively long. "Additionally, this bird is known for forming lifelong pairs, hence symbolizing a happy marriage." Cranes and herons are very commonly used motifs, both as birds standing in water and in flight, both individually and in groups.

Karasu – Crow

The mischievous crow is seen as a bad omen. It is associated with fire, as legend has it that it flies close to the sun and therefore has black, scorched feathers. Crows, due to their color, are perfectly suited to lacquer painting using techniques that utilize black lacquer and imitate sumi-e painting.

Taka – Falcon

'Taka' in Japanese also means heroism, and indeed the falcon symbolizes power, boldness, and courage. It has sharp claws and beak, keen vision, speed of flight, and intelligence.

Sagi – Heron

This bird is associated with success and luck. It is most often depicted with elements symbolizing summer and water. Sometimes seen as a messenger of sages or gods.

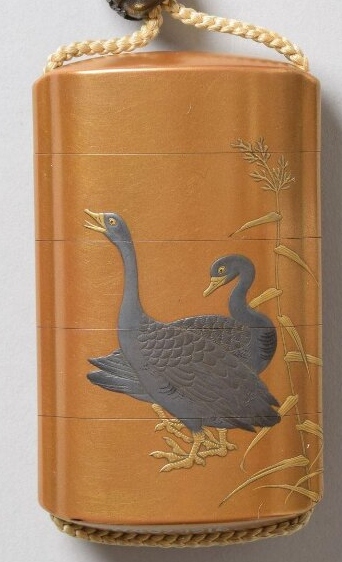

Oshidori – Mandarin Duck

The mandarin duck is a favorite among lacquer artists because its plumage suits the techniques used and also because the duck represents marital affection, mutual understanding, and love. Therefore, depictions always include a pair of ducks. It is believed that a pair of ducks stay together for life, and if one dies, the other does not pair again and mourns. Hence, ducks are seen as delicate, kind, and caring.

Ugisu – Nightingale

A small bird cherished for its song and romantic associations. It is considered to be the herald of spring's arrival. Interestingly, the nightingale is also associated with religiosity because its song suggests the intonations of a Buddhist sutra.

Fukuro – Owl

"The owl is a symbol of family harmony, as both parents care for their offspring. In Western cultures, the owl symbolizes wisdom, but in Japan, it is associated with luck. Additionally, because an owl can turn its head 360 degrees, it is also used as a symbol of commerce. One must have eyes all around the head to succeed in business.

Kujaku – Peacock

The peacock eats venomous snakes and insects, therefore it is considered very strong and resilient. It repels misfortune and is also a symbol of numerous offspring and many generations within a family.

Kiji – Pheasant

One of the most beautiful birds, appreciated by lacquer artists. Depicted alongside blooming cherry blossoms, it symbolizes regal beauty. As a messenger of the goddess Amaterasu, it is a bird of good omen and represents parental devotion, as it is said to willingly risk its life to save its young.

Chidori – Plover

Small birds often found in large flocks. Depicted as rising just above the waves, they symbolize the struggle to stay above the storms and conflicts of life. Often portrayed in a stylized manner.

Sparrow (Suzume)

Sparrows, often seen in flocks, symbolize abundant harvests and success in Japan. They also represent strength and the will to survive, as they can endure the harsh conditions of a cold winter. Their images are primarily used in autumn and winter designs.

Wild Goose (Gan)

The flight of wild geese is a symbol of autumn because they migrate at the same time every year. They are compared to a loyal spouse, and seeing them is considered a lucky sign. Their swift and sure flight symbolizes vigor and vitality.

NATURAL PHENOMENA, ATMOSPHERIC ELEMENTSAND LANDSCAPES

In lacquer art, the sun and the full moon, often in their phases, are commonly depicted. Techniques include inlays of snail shells or metal foils. Many lacquer decorations feature two elements associated with moisture: water and clouds. These are mainly represented as meandering rivers or coastal seascapes, and clouds may appear singly or in groups, with clouds often detailed or only sketchily indicated. Clouds frequently appear alongside mountains, dragons, and demons. Various methods of symbolically representing water and clouds exist, such as those detailed in the "Pattern Sourcebook: Nature" by Shigeki Nakamura, which includes 250 water wave and cloud patterns. These patterns range from realistic to geometric, like the seigaiha pattern—circular wave crests overlapping like fans, symbolizing the boundless sea and the wealth it brings, thus associated with good fortune. Water is also depicted as rain, subtly indicated by parallel lines, and occasionally as snow, lightning, and fog.

Wind is usually indicated indirectly, by the bending of grasses or fluttering leaves.

Landscape

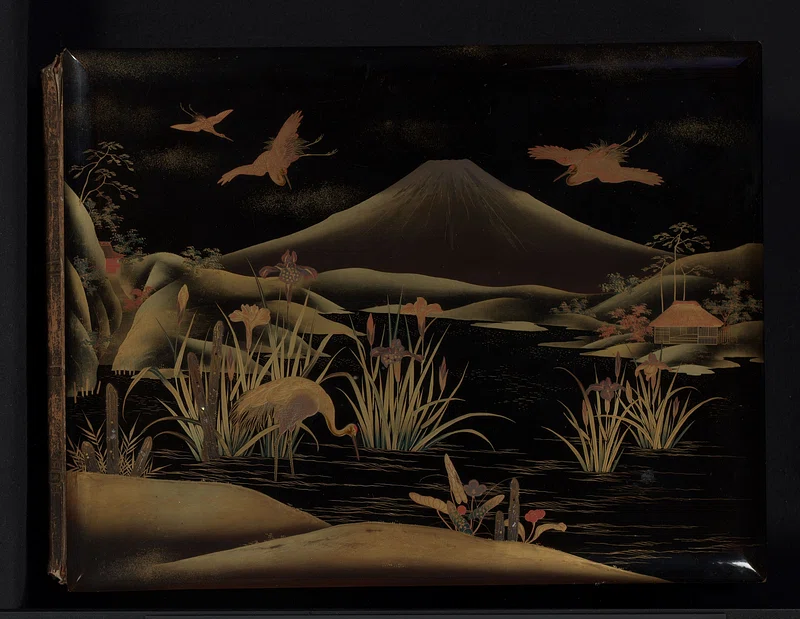

In many lacquered works, the dominant theme is "views". Earlier images are more symbolic, while later ones are more realistic. They may include objects such as thatched huts or manors, meadows, and less commonly, forests. Flowing water is typically woven into these decorations. Favorite representations include wind-warped pines on rocks. Mountain landscapes are a common theme, built on the principle of "distant mountain" and "near mountain". The former depicts a mountain or mountain range in the distance with closer perspective elements, while the latter often shows a portion of a rock with overhangs, accompanied by various plants and sometimes a waterfall. Seascapes with ships and boats are also depicted.

Fuji

Mount Fuji is a favorite subject in Japanese art, its iconic conical shape and snow-capped summit making it a gratifying motif, not to mention that it is one of Japan's symbols.

ITEMS ADN PROFESSIONS

Weapons and Armor

A commonly encountered motif is the tsuba (sword handguard), depicted using lacquer techniques that mimic metals. Swords, knives, and pieces of armor (such as helmets) also appear frequently.

Everyday Items

These can include fans, furniture, toys, dishes, tea ceremony utensils, screens, and tools such as agricultural implements and transportation means (palanquins, carts, parts of carts like wheels), flags, and games like "Go".

Musical Instruments

Instruments such as taiko (drums), fue (flutes), koto, biwa, shamisen (stringed instruments), and bells are often depicted.

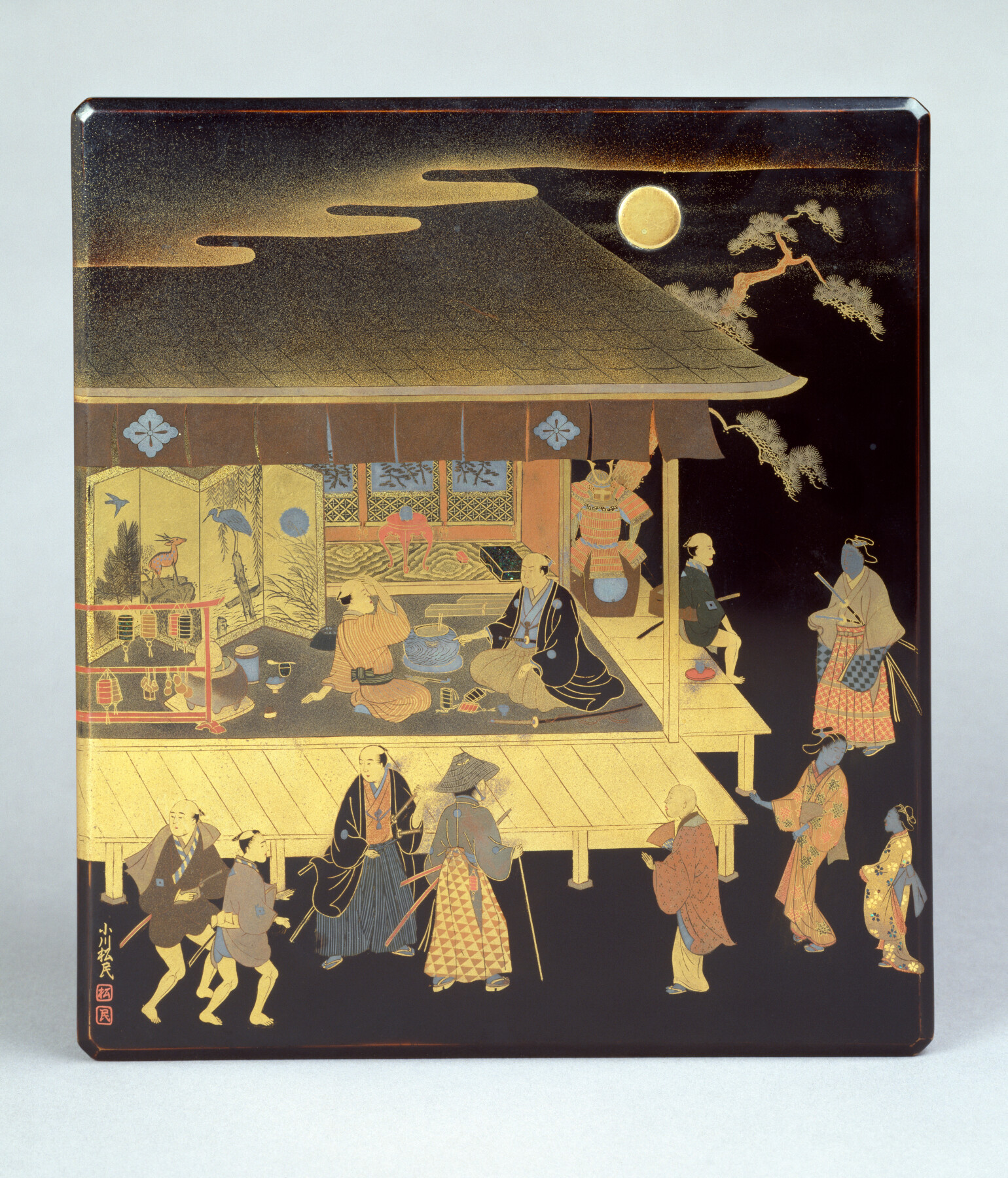

Genre Scenes

Lacquer decorations may feature scenes showing people at work. These include peasants planting rice, operating irrigation devices, performing maintenance tasks, blacksmiths, craftsmen, and also actors and dancers.

SYMBOLS AND ABSTRACT REPRESENTATIONS

Mon – Clan Emblems

Since the 18th century, the clan emblem became a popular motif due to its elegant appearance and as a way of promoting a "family brand." There are many such emblems (for instance, in Hugo Gerhardt Strohl’s "Japanese Heraldry" from 1906, you can find several hundred family symbols and their variations), but the most frequently encountered are the imperial crest (16-petal chrysanthemum), the Tokugawa clan emblem (three hollyhock leaves facing each other), the Abe clan emblem (two crossed feathers), and the Takeda clan emblem (four black diamonds).

Calligraphy, Kanji, Poetry

In lacquerware, kanji characters are sometimes woven into the background of an image (a figure, landscape, or genre scene), occasionally as "hidden" elements, forming parts of a poem or aphorism, typically sprinkled in the takamaki-e technique. Standalone writings are very rare.

Abstract Themes in Lacquer Art

Various abstract themes range from patterns, filigrees, and mosaics to (rarely) unclassifiable images composed of spots or shapes forming abstractions.

Buddhist Symbols

Symbols associated with Buddhism are naturally present in lacquer decorations. These can include the fish (gyo), lotus (hasu), endless knot (nade-takara-musubi), umbrella (karakasa), conch shell (hora), and wheel (rimbo).

Additional Symbols in Lacquer Decorations

Other symbols used in lacquer art include the mirror (kagami), swastika (manji), scale (fando), key (kagi), straw raincoat (kakaremino), scrolls (makimono), the comma-shaped tomoe, Torii gate, and others.

OTHER THEMES

In the vast diversity of ideas found in art, there are themes that frequently recur and have been replicated in many ways, as well as rarer depictions due to the subject matter or fashion and trends of a particular historical period. For example, the "namban" motif was popular at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. It signified the "southern barbarians," as the Portuguese sailors and missionaries arriving in Japan were called. To the Japanese of that era, these newcomers were an exotic sight due to their ships, attire, behavior, and equipment, which were different from the local norms. This interest was also reflected in lacquer art.

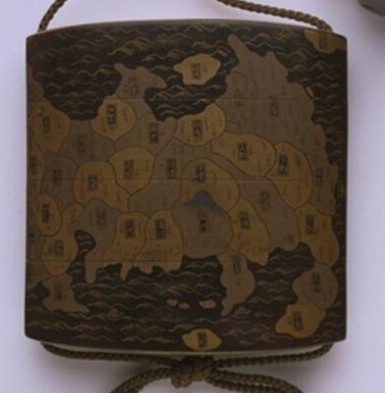

Maps are another motif found, for example, on inro—simplified plans of the Japanese islands or specific areas.

Scenes from everyday life are another theme. While very common in painting, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, they are rarer in lacquer art. Images of female silhouettes and faces, very popular in prints and paintings, appear sporadically in lacquer work.

Additionally, humorous references to specific situations, stories, or legends are a theme. Animals are often depicted in typical human attire and behaviors. The subject matter is humorous, describing, for instance, a fight between a rabbit and a frog or anthropomorphic rabbits and monkeys bathing and preparing for some ceremony.

In Japanese representational art, lacquer is often linked with painting because prominent artists usually engaged in various disciplines (for example, Shibata Zenshin was a painter, lacquerer, and ceramicist). Thus, the motifs used in paintings are similar, though in painting, due to the generally larger format of the works (especially compared to inro or netsuke), there were much better conditions for elaborating on a theme or even tackling subjects whose details would be very difficult to convey when creating miniatures. Indeed, there are lacquers with incredibly precise, microscopic details, but most use symbolism and simplified imagery.

The choice of motif was also important depending on the type of object. On larger surfaces like boxes, furniture, or screens, the images could be more expansive (landscapes, more detailed representations), while on smaller items like inro, netsuke, or combs, the decorations necessarily had to consider the small dimensions. The type of product also influenced the themes; for example, boxes for scent game/incense tools typically had plant decorations, and boxes for writing utensils were painted with various objects, animals, and literary motifs (brushes, feathers, birds, genre scenes), although almost every motif appeared with greater or lesser frequency.

As I've mentioned before, the only limits for creators were imagination and the technical possibilities of presenting the motif. Over several centuries, likely hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of lacquered items were "produced." Relatively few have survived to our times, and they are available to the public in a limited capacity. Therefore, undoubtedly there are many more examples. Due to copyright laws, only a few of these can be directly cited in the form of images, hence I direct interested readers to online resources. I hope this "sui generis" guide can facilitate the appreciation of these works.

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/piotr.faryna

However I do not intend to collect, process or share personal data in connection with running this website, but if something like this happened, I hereby declare that: the personal data administrator is Piotr Faryna. Your data may be made available/transferred only in the cases indicated in the regulations at the request of authorized institutions. You have the right to request to view, change or delete your data.

Kontakt

Menu

Mój profil

Strona www stworzona w kreatorze WebWave.