Piotr Faryna ピョートル・ファリナ

1. Japanese lacquer part. 1 general information

The literature on Japanese lacquer and published scientific research is quite limited, with bibliographies on the topic typically listing only about a dozen entries. This scarcity can be attributed to the specialized nature of this subject. Japanese culture boasts a rich legacy of arts that span a wide array of disciplines, including literature, theater, painting, calligraphy, sculpture, architecture, weaving, ceramics, weaponry, handicrafts, and many others.

Unlike European art, Japanese art utilizing lacquer doesn't sharply differentiate between fine arts (higher, absolute) and applied arts (practical, decorative). In Japan, beauty transcends the medium or classification. In contrast, Western tradition often relegates works with utilitarian purposes to the realm of crafts, regardless of their aesthetic value—a distinction disparaged by critics and excluded from the fine arts category. However, such divisions are absent in Japan, making lacquerware just one among countless forms of artistic expression involving various materials and decorations.

Recent trends suggest a slight shift towards Western perspectives in Japan. Yutaka Tazawa and other authors of 'History of Japanese Culture in Outline' note that Koetsu (1558-1637) was the first Japanese decorative artist to be distinctly recognized apart from craftsmen, an opinion that might undermine the contributions of earlier lacquer masters.

In Polish, only a few monographs on this subject exist, while the English language boasts several dozen. There are also numerous studies in Japanese, though they are less accessible due to translation challenges and the complexity of language research—issues now somewhat alleviated by advanced machine translation technologies. The content in this article (and others on this website) aims to popularize the topic and synthesize key information. Having had nearly 20 years of hands-on experience with this material, I occasionally offer insights based on practical observations

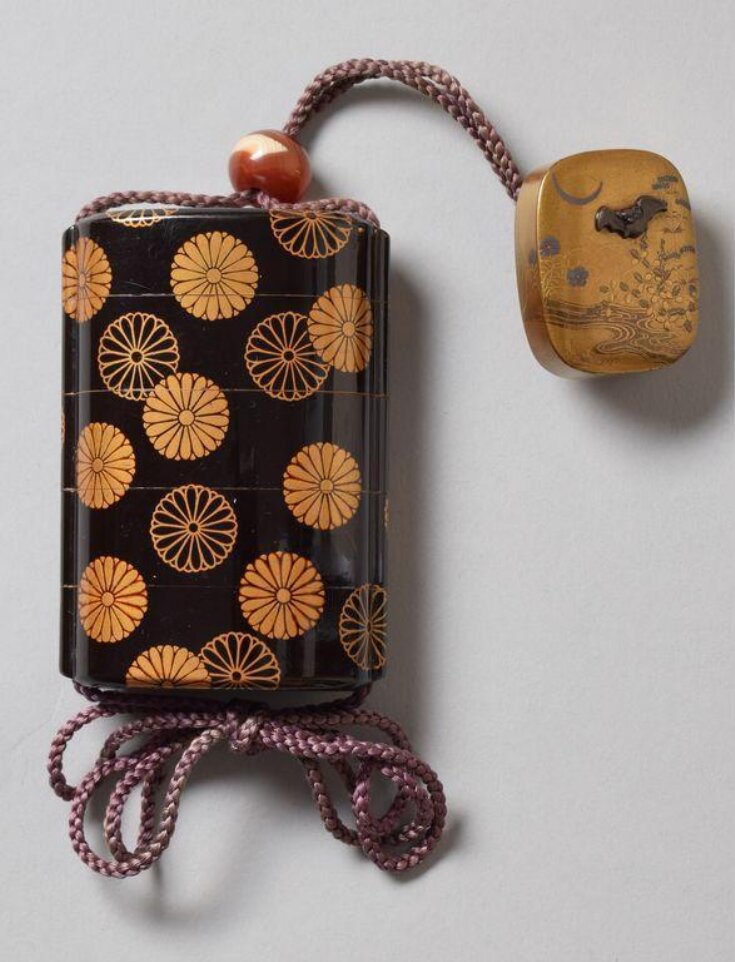

Today, Japanese lacquer as an artistic medium primarily finds its place in museums and among collectors. Although there are still active workshops in Japan—such as the Wajima and Kanazawa centers known for creating lacquer dishes, Aizu for producing boxes, Kishu for chopsticks, and various companies that decorate pens and jewelry (for more details, see Bibliography III)—these primarily focus on high-level commercial production rather than creating what would traditionally be considered fine art. Nonetheless, several artists continue to work with lacquer in both traditional and modernized techniques. Notable practitioners include Kojiro Yoshiaki, Takuya Tsutsumi, and Tatsuo Kitamura in Japan, as well as Gen Saratani, Nobuyuki Tanaka, and Yoshio Okada in the USA. However, traditional items showcasing the highest level of artistic craftsmanship, like inrō or various types of bako, which reflect nearly a thousand years of tradition, are no longer produced, to the best of my knowledge.

For enthusiasts of lacquerware and aficionados of Japanese aesthetics, there are three main avenues to appreciate this art form.

The most exclusive is collecting original works of art. These can be acquired at auctions, antique shops, and markets, with prices varying widely. While it is possible to find an inrō for as little as $100, a fine piece typically starts at around $1,000, with highly valuable items reaching into the tens of thousands."

The second method involves visiting museums. Globally, numerous museums house significant collections of Japanese lacquerware. Noteworthy examples include the Tokyo National Museum in Japan, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Kyoto National Museum in Japan, Musée Guimet in Paris, The Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The Victoria and Albert Museum, given its accessibility, is particularly notable for those in Poland. There is also the Museum für Lackkunst in Münster, Germany, which focuses on lacquer art from various countries, though its Japanese lacquer exhibits may not meet all expectations. In Poland, the National Museums in Krakow, Warsaw, Poznań, Wrocław, and several smaller institutions hold Japanese lacquerware, with some pieces of remarkable artistic value, although not all are on permanent display.

The third avenue is online exploration. Platforms such as Pinterest feature numerous posts showcasing Japanese lacquer items like inrō, tebako, suzuribako, and netsuke, providing widespread access to these masterpieces. Additionally, YouTube hosts many videos related to Japanese lacquer art, with links often included within articles.

Lacquer art is an extremely labor-intensive process that demands patience, precision, creativity, and extensive knowledge. The materials required are scarce and often costly. Techniques such as those needed for creating mock-ups involve intricate knowledge of the craft, specialized materials, and tools. Secrets of the trade are closely guarded by masters, often making the learning process a challenging trial-and-error journey. From my own experience with experimenting with lacquer, I have learned that, despite the challenges, the satisfaction derived from pursuing this art form is immense, regardless of the outcome

obraz wygenerowany przez ChatGPT4/Dall-e

-

Definition and general remarks

Lacquer (Japanese: 'urushi', うるし; English: 'lacquer'; French: 'laque'; Russian: 'lak', лак; German: 'lack') is a natural resin obtained from the sap of sumac trees—Rhus vernicifera/Rhus verniciflua, known in Japan as urushi no ki. These trees are primarily found in Japan, China, and Korea. While cultivated on plantations, the highest quality sap is sourced from wild sumacs in Japan. This sap, both in its natural form and after being processed technologically, is used to coat various materials and objects, enhancing their durability and decorative appeal. The term 'laka' often gets confused with 'shellac,' derived from words like 'lakk', 'laksha', and 'laca', which refer to a different substance used for surface finishing (2)(5).

In Europe, one of the earliest comprehensive studies of lacquer properties was conducted by John J. Quin, Her Majesty's consul in Hakodate, in a report from 1882 (3). Around the early 20th century, detailed chemical analyses of the raw material were performed by Alviso B. Stevens among others (4). Quin also brought to Europe a collection of over 40 bottles containing various types of Japanese lacquer, along with sample materials, boards, and tools, which are displayed at the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew, London (X). Recent research, including studies conducted in Germany, provides a detailed characterization of lacquer's primary component, urushiol (1).

Far Eastern lacquer is a unique material. With a consistency akin to thick oil paint, it applies smoothly with a brush in thin layers and has very high viscosity. It is also used as a binder in the art of ceramic repair (kintsugi).

Lacquer does not dry by air contact or evaporation. Instead, the urushiol it contains polymerizes under specific conditions of temperature and humidity. Once cured, lacquer becomes highly durable, resembling modern plastics and is resistant to acids, alkalis, water, and other solvents. It withstands high temperatures and mechanical stress, can be sanded and polished to a high gloss for a mirror effect. After further processing and the addition of other ingredients, lacquer is available in various formulations tailored for specific uses (see below: 'Types of lacquer'). Its polished surface achieves a 'painfully perfect' finish, devoid of any flaws (6). European attempts to replicate lacquer using other materials largely failed, although the so-called 'European lacquer" based on shellac, oils, etc. ingredients.

Due to the properties of urushiol, uncured lacquer can cause allergic reactions in some individuals, leading to ulcers and other skin and respiratory issues. It is advisable to exercise caution and use protective gear when handling lacquer. Desensitization methods include one involving crushed small freshwater crabs, and prolonged exposure to urushiol may lead to the development of natural immunity (5). Cortisone-based medications are also known to be effective in treating reactions. The reaction to fresh lacquer typically starts with an unpleasant tightening of the skin, primarily on the face and hands, followed by swelling and the formation of red spots that can develop into blisters. However, these symptoms are relatively mild and do not pose a significant health or life threat (4).

Urushi sap is harvested, much like resin, by making precise cuts in the bark of trees, ideally those around 10 years old. The collection process, known as urushi kaki, occurs during the summer months from June to September. The sap is extracted from the trunks and branches of trees. Collectors, known as kakiko, cover extensive areas since the sap yield is limited to about 200 grams per tree (IX). They use specialized tools including curved knives (kakigama), various blades, spatulas, and wooden cups (1)(3). Alviso B. Stevens notes that an average collector would manage between 600-800 old trees or up to 1,000 younger trees (4). Tree trunks and branches no longer viable for further sap extraction are soaked in hot water, and then the sap is collected by additional cutting and squeezing, yielding a product with slightly different properties than that extracted directly from the trunk

The initial processing of the white sap involved setting it aside to allow impurities to settle to the bottom of the container. The raw lacquer sap was then placed in a warm area and stirred to evaporate the moisture it contained, which typically ranges from 25-30%. Efforts were made to reduce this moisture content even further. The sap was filtered to remove wood fragments, dust, insects, and other contaminants by passing it through fabric and soaking rags, which attracted smaller impurities. This careful filtering and subsequent mixing resulted in a purified product called ki urushi. Organic oils, resins, and dyes were added depending on the intended use of the lacquer, with common diluents being powdered camphor and turpentine. Historically, lacquer was stored in paper tubes or wooden containers, but today it is packaged in metal tubes or larger paint-like cans.

In modern facilities, lacquer sap collected from the forest is maintained at a controlled temperature year-round. It is heated in a water bath—a contemporary substitute for sun exposure—and cotton balls are used in the vat to knead out impurities from the urushi juice. The lacquer is then centrifuged and filtered. Subsequent processes include nayashi, which involves the thorough homogenization of the varnish particles by mixing at various speeds and durations, and kurome, which adjusts the moisture content and viscosity through careful heating. It is crucial to avoid excessive temperatures that could degrade the lacquer's properties. Finally, specific treatments are applied to produce different types of lacquer, achieving desired finishes such as glossy or matte, transparent or colored, and varying degrees of thickness and stickiness.

At: https://youtu.be/lbXKIwLGwNA (Youtube) you can watch a movie about obtaining lacquer sap.

-

History

The origins of lacquerware are shrouded in mystery, yet are progressively being unveiled through new archaeological discoveries. Various sources offer differing timelines for these findings.

According to a study of wood from a site in Fukui Prefecture, it was found that the wood came from a lacquer tree dating back about 12,000 years, making it the oldest known lacquer tree in Japan. This site and others from the early Jōmon period, approximately 7,000 to 5,500 years ago, have yielded numerous artifacts, including pottery, wooden containers, combs, and jewelry such as earrings, all coated with lacquer tree sap. This indicates that the use of lacquer dates back to at least this period, if not earlier, as noted by Hidaka Kaori, a professor at the National Museum of Japanese History (IV).

Further findings at the Kakinoshima site in Hakodate, Hokkaido, suggest the use of lacquerware in Japan as far back as 9,000 years ago (III). According to Wikipedia, the technique of lacquer decoration in Japan emerged around 5000-4000 BC. Ann Yonemura reports that evidence of lacquer use during the Jōmon period, specifically in the 1st millennium B.C., has been documented through archaeological findings (26). Zofia Alberowa adds a historical perspective, stating, 'The beginnings of the history of Japanese lacquer are lost in the darkness of the time of the gods. The Nihongi Chronicles, compiled at the beginning of the 8th century, provide information about the knowledge of lacquer and its artistic use as early as the 4th and 3rd centuries BC' (6)

In the book "Japanese Lacquer" by Dorota Róż-Mielecka we read: "Based on recent archaeological finds, it can be assumed that objects were covered with lacquer already in the middle of the Jōmon era, i.e. 4 or 5 thousand years ago" (although in a footnote the author states that as for researchers do not agree on the origins of this branch of artistic craftsmanship in Japan). These included "trays decorated with black or red lacquer, bamboo baskets, combs, hairpins, jewelry and clay vessels. In the Yayoi period (from the 4th century BC to the 4th century AD), lacquered armor appeared, in the following centuries, the so-called barrow culture (Kofun period, approx. 4th-7th centuries), coffins. (...)” (2).

“The oldest examples of lacquered items date back to the early Jomon (c. 3500-3000 B.C.).” - the book "Urushi no waza" contains an extremely rich description of the history of Japanese lacquer, starting from prehistoric times, through all eras, up to the Edo period (1).

ChatGPT4, when asked about the oldest lacquering artifacts in Japan, states that "The practice of lacquering in Japan dates back to the Jōmon period (approximately 14,000–300 BC). The most ancient examples were discovered at the Kakinoshima 'B' Excavation Site in Hokkaido. These artifacts date back to the Final Jōmon period, roughly 5000 years ago. These findings are often documented in academic research published in journals such as the 'Journal of Japanese Archeology' or in exhibits and collections of museums specializing in East Asian history, like the Tokyo National Museum.” (ChatGPT 4, query February 3, 2024)

Melvin and Betty Jahss discuss the early history of lacquerware in their writings, noting that the first mentions of lacquer producers and the establishment of the Imperial Lacquer Department occurred during the reign of Emperor Koan in the 3rd-4th centuries AD (7). This period marks a significant development in the institutionalization of lacquer art in Japan. Interestingly, the Jahss suggest that lacquer art was originally used in China and was imported to Japan. Conversely, Gunter Heckmann argues that lacquer art developed independently in Japan and should be considered a Japanese invention (1). This divergence in views may stem from the early utilitarian applications of lacquer, primarily used for surface protection before its decorative qualities were emphasized. The debate continues over how much the decorative aspects of lacquer art were influenced by continental trends and how much they originated within Japan.

It is widely accepted that lacquer has been used in Japan for at least 5,000 years to protect and cover surfaces, and it has been employed for decorative purposes for approximately 1,500 years.

The broader history of Japanese lacquerware is well-documented by various scholars. Martin Feddersen provides a detailed account (19), while U.A. Casal offers insightful reflections on the subject in his 1959 article, presenting a rich historical narrative. Below are some selected excerpts that encapsulate his findings, based on his work (28).

“ Broadly, Japanese lacquer art can be segmented into three distinct periods: the ancient period, spanning from the Nara period to the end of the Fujiwara era (approximately 700 to 1200 CE); the middle period, which includes the Kamakura and Ashikaga eras (1200 to 1600); and the Tokugawa or Edo period (1600 to 1850). The first period was characterized by a reliance on Chinese conventionalism and the limited technical capabilities of the time. From the 8th to the 11th century, materials such as braid and leather were commonly used as bases. The influence of Buddhism significantly supported the development of the arts, including lacquer techniques. By the mid-12th century, significant advancements had occurred: varnish and gilding techniques had improved, leading to a more refined, albeit still imperfect, methodology. The artistic designs transitioned from thin, outlined fills to a more robust and densely packed style, introducing backgrounds filled entirely with fine gold powder (fundame).

During this time, hemp fabric layers were utilized to stiffen surfaces, although the finish was often rough and the varnish sometimes impure. Symmetry, a dominant element of traditional Chinese ornamentation, began to be eschewed as Japanese artists sought their own unique decorative expressions. The designs became asymmetrical, shifting the visual weight from the central or lower parts of the panels, moving towards a style that favored grace and rhythm over static balance. Technological advancements continued with the introduction of relief techniques like takamaki-e, which supplemented the earlier flat hiramaki-e and togidashi-e techniques. Silver powder, once commonly used alone or alongside gold, fell out of favor as various types of gold came to dominate the decorative elements. The Muromachi era (1392-1490) marked a pinnacle in the evolution of lacquer work, shedding the last vestiges of rigidity. This period refined the balance and dynamism in lacquer decoration, with artists using exaggerations in detail to evoke stronger emotional responses and creatively employing empty spaces for artistic counterpositions. It became fashionable to enhance the poetic essence of a landscape by integrating silver ideograms that referenced well-known verses.

Regrettably, the flourishing artistic progress described previously was preceded by a turbulent century marked by confusion, poverty, disease, and destruction, known as the Sengoku Jidai or the period of civil wars (1490-1600). During this time, painters and artisans continued their work as best they could, but the period was characterized by practical stagnation or even regression until Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-1598) rose to power. Hideyoshi played a pivotal role in reviving the arts; he encouraged both samurai and common citizens to invest heavily in art, particularly items that could be utilized during the tea ceremony, of which he was a fervent advocate. His enthusiasm extended to taking a personal interest in various classes of artists and craftsmen, rewarding them handsomely for exceptional work, and even going so far as to import specialists from the continent to enhance local skills. Under his influence, craftsmanship across the board saw significant improvements once more.

The exquisite virtuosity of the gold lacquers from Hideyoshi's era has maintained its prominence up to the present day. A distinctive feature of the lacquer work from around 1600 is the 'diagonal line' technique. This approach positioned one lower corner as the focal point, compressing the image into a pronounced triangular shape, akin to a hypotenuse, that stretched from the opposite lower corner to a higher point on that side. The remainder of the panel, often more than two-thirds of it, was left empty or nearly so, occasionally adorned with minimalist elements such as a high moon or a solitary bird to capture focus.

During this period, family coats of arms (mon), which had previously served merely as identification marks, evolved to become central elements of lacquer decoration. The transformation from the rough contours of the eighth century to the refined products of the sixteenth century illustrates a slow yet profound technical and artistic evolution. Indeed, the change witnessed between gold lacquer work from, say, the 9th century and the early 16th century is less substantial than the developments seen between the late 16th and early 18th centuries, following the Momoyama period's impetus and subsequent social reorganizations.

One notable figure from Hideyoshi's time, Hon'ami Koetsu (1558-1637), left a significant mark on the lacquer tradition. Koetsu pioneered a highly personal style characterized by the use of mother-of-pearl and tin inlays, along with sketchily applied surfaces of gold lacquer, in an innovative and unconventional manner.(...)

At the dawn of the 17th century, with Tokugawa Ieyasu's dominance marking the beginning of the Edo period, Japan entered a phase of relative peace lasting 250 years after the tumult of 1615. This era of tranquility naturally fostered prosperity, from which all arts and crafts, including lacquer art, greatly benefited. Japan’s social structure underwent rapid and profound changes, deeper than even those anticipated in Hideyoshi’s time. While a detailed exploration of these processes is beyond the scope of this discussion, it is essential to highlight the main features relevant to the evolution of lacquer art.

During this prolonged period of peace, the once-dominant military class, apart from the central administration, lost much of its former power. It became more effete and meticulous, engaging in competitions of luxury rather than valor. As the aristocracy’s exclusive patronage of the arts waned, replaced by a new, burgeoning purchasing power, the classical respect for tradition gave way to more naive yet expressive styles. This shift led to a decline in the former splendor from an academic standpoint, suggesting a regression. However, it's important to acknowledge that by the end of the Ashikaga reign, classical styles had become somewhat stereotypical and sterile, and the introduction of vibrant plebeian influences infused lacquer art with a new, unprecedented vitality.

The lacquered objects from the Tokugawa period display a vast spectrum of quality and creativity, and here we can only provide an overview. The first half of the 17th century largely retained the Momoyama style but expanded upon it considerably. Gold backgrounds began to replace monochromatic ones, and the use of kiri-kane (cut gold) and minor inlays became more prevalent, with additional colors being introduced. This period was marked by a surge of activity and creativity; while moderation was still the prevailing theme, the decorations became more thoughtful, refined, and naturalistic.

A notable characteristic of this brief but significant period was the extension of designs beyond a single panel to adjacent surfaces, and the meticulous treatment of even the rarely seen parts of an object. Themes varied widely, but serene gardens and scenes from classical romances, particularly the Tale of Genji, were favored. Landscapes, however, were often reduced to views one might see through a window, losing some of their grandeur.

The concept of purity in design gradually gave way to a richness of composition. Although the elaborate ornamentation was delicate and strategically placed, it began to sow the seeds of decadence and triviality that would dominate a century later. The use of inlays became more pronounced, and the gradation of gold powders brought about significant enhancements in shading, contributing to a greater depth and complexity in the artwork."

This version aims to convey the dynamic changes and cultural shifts influencing lacquer art during the Tokugawa period, emphasizing both the artistic advancements and the eventual complexities that emerged.(...)

Due to a series of crop failures, physical disturbances, and economic downturns, the latter part of the 18th century saw a significant downturn in the production of noteworthy lacquer pieces. During this period, there was a marked shift towards prioritizing the quantity of goods over their quality. The demand for lacquer surged unexpectedly, necessitating that all available craftsmen work in shifts and large workshops be utilized to meet the production needs. This sudden shift had a detrimental impact on both the techniques employed and the overall craftsmanship.

The themes of the lacquer pieces from this era were less discerning, focusing on motifs that could be completed quickly, with flowers, butterflies, and rudimentary landscapes becoming predominant. The artistic compositions of this time lacked depth and intricacy, and finer details were largely overlooked. Fortunately, the decline in artistic standards did not extend far beyond the confines of the shogunate palace.

The period between 1804 and 1830 marked a renaissance in gold lacquer art, spurred by the collecting fervor of both the nobility (daimyō) and affluent townspeople. This new wave of enthusiasts demanded the highest quality workmanship, perfect proportions, and a richness of detail designed to captivate and enchant the viewer. This era is renowned as the golden age of inrō, netsuke, tsutsu, sakazuki, and even combs, whose makers became highly esteemed. These items were not only displayed with pride among collectors but also exchanged as valued gifts. Craftsmen during this time mastered their materials to such an extent that their works, featuring landscapes, figures, flowers, and insects, achieved a level of perfection sometimes criticized as 'overwrought studies'. Yet, these creations represent some of the most precise and elegantly crafted lacquers ever made, showcasing almost unbelievable technical skill.

This newfound appreciation for detailed and refined lacquer work also permeated the upper echelons of society, despite their traditional disdain for what they considered 'plebeian art'. Over the century and a half since Hideyoshi's era, the purpose of lacquered objects had transformed from predominantly ceremonial uses to expressions of beauty and the joyous spirit of the people. Innovations such as Gyobu-nashiji highlighted the brilliance of gold lacquer, while the use of fine inlays and Somada techniques, which replaced the traditional Chinese painting style with mother-of-pearl inlays and pure sheet gold, flourished. Additionally, Sumi-e techniques were adopted to emulate famous ink paintings against gold or silver backgrounds, enriching the variety of colored lacquers and often replicating the texture of wood on the surrounding surfaces. Carved lacquers became more intricate, covering a broader range of subjects. This period is celebrated as the third pinnacle of lacquer artistry.

However, the final decades of the Edo period saw a gradual decline in the craft. While the lacquer work of this time retained much of its elegance and color, the precision in execution and the creativity in composition waned. The artistic verve that had fueled previous generations began to fade; though technical knowledge was advanced, the market was increasingly dominated by rushed and inferior products.(...)

With the Meiji Restoration in 1868, a social upheaval disrupted not only the established standards of art but also the ethos of fine craftsmanship. The traditional supporting classes lost their status and could no longer patronize artists, while the newly wealthy, though eager to spend, often lacked the cultural education to appreciate traditional art forms. Foreigners, many of whom had refined tastes, were frequently misled into purchasing items that appeared the most 'oriental'—typically those that were gaudy or overly intricate. Meanwhile, others, driven by the potential for quick profits, saw opportunities in new markets and imposed their preferences, pricing, and deadlines on artists who, needing to make a living, felt compelled to comply.

This era saw the emergence of a new class of painters whose work—tacky, gaudy, and sentimental—catered to the tastes of an uninformed international audience, quickly becoming a major export. Regrettably, these styles were just as eagerly embraced by the Japanese public, who, under the misconception that Western appeal equated to sophisticated taste, favored designs featuring Mount Fuji, flying cranes, cherry blossoms, geishas, boats, and dragons. These motifs were stripped of any poetic nuance that had once enriched them, reduced to mere representations of the 'exotic' elements that early Western writers found so quintessentially Japanese.

The latter part of the 19th century and the first three decades of the 20th century thus marked a period of artistic confusion, lacking clear direction, despite the presence of exceptional talents like Shibata Zeshin (1807-1891). The economic downturns during and after subsequent wars further exacerbated the decline, making the production of high-quality lacquer art prohibitively expensive and depleting the ranks of wealthy patrons. The finest remaining artists, many of whom were advanced in age, found themselves relegated to working in souvenir factories or teaching in craft schools, far from the artistic pursuits they had once dominated."

Traditionally, in the history of Japanese art until the end of the 19th century, the main periods of ancient Japan are distinguished, the so-called eras: Jōmon, Yayoi, Kofun, Asuka, Nara, Heian, Kamakura, Muromachi, Momoyama, Edo and Meiji. In this order, the most important features of lacquerware in particular years can be briefly presented.

Jōmon (ok. 14 000–300 p.n.e.):

• The use of lacquer mainly for conservation purposes of ceramic, wooden, bamboo, shell and horn products.

• The beginnings of using techniques to distinguish layers (lacquer primer mixed with sawdust (urushi kokuso) and top coating), and at the end of this period also several layers applied after smoothing the previous one).

• Use of both raw lacquer and those with admixtures (black and red lacquer).

Yayoi (ok. 300 p.n.e.–300 n.e.)

• Generally decreased use of varnish.

• The beginnings of using lacquer to cover and decorate everyday objects such as combs, handles, bows, shields, elements of armor, wooden bowls, etc.

• Further priming layers of lacquer mixed with clay (jinoko) were introduced.

• Simple decorative patterns in geometric form appear.

Kofun (ok. 300–538):

• The production, use and level of technology of lacquered products are clearly decreasing

• The materials used were mainly wood and leather, rarely using primer, mainly painted with black lacquer, layering one on top of the other and finishing with transparent lacquer.

• As in previous periods, decorations were sparse, indicating the predominant purpose of lacquer to protect various objects against damage, moisture and rot.

Asuka (538–710):

• The introduction of Buddhism had a major impact on lacquer art. From this period, we can talk about the artistic use of lacquer, although perhaps not in a pictorial sense, but rather in a figurative sense.

• Use of new materials – paper and fabrics.

• Return to old techniques and development of new ones used for various types of boxes-containers, sarcophagus and urn decorations.

• Production of the "dry lacquer" technique (kanshitsu), developed later in the Nara era, which involved placing rags soaked in lacquer on a clay mold, and then removing the clay after the lacquer had hardened. Another variant of kanshitsu used wooden skeletons.

• An increasing number of lacquerware products are related to the religion of Buddhism.

• The use of lacquer to cover larger surfaces, such as gates, walls and pillars in temples. “Lacquer was used mainly as decoration for buildings, Buddhist depictions, and even priests' robes” (7). However, artifacts from this period produced in Japan are often difficult to distinguish from those imported from China.

Nara (710–794):

• Inflow of ideas, products and technologies from China. The technique of carved lacquer (sometimes simply called "Chinese lacquer" tsuishi) appeared.

• The use of specialized materials as a base (cyprus wood - hinoki, cedar-cryptomeria - sugi) instead of the often previously used leather.

• Technically, the application of lacquer became more and more sophisticated, various layers of ground (shitaji) were laid, and procedures were created that were used practically throughout the subsequent history of lacquer.

• Decoration of cult objects, Buddhist sculptures, gigaku masks, bowls, bowls, boxes (bako), furniture, toiletries, musical instruments.

• Use mainly of black and transparent varnish. Metal elements appear in the decorations - mixtures of various substances with powdered gold and silver, as well as covering with metal foil. There is also the use of mother of pearl (raden) and other materials, such as turtle shell. Gilding was done by painting a mixture of lacquer and metal powders with a brush, but for the first time in this era techniques were used that were the ancestors of the "powdering" technique - maki-e, which was characteristic of Japanese lacquer in later periods.

• In the mid-7th century, Emperor Kotoku creates a special office employing the best lacquer artists (7), and a little later a lacquer guild is established.

• Decorations appear in the form of representations of plants and various geometric patterns.

• Some painters are starting to sign their works. Some authors claim that what survives in lacquerware from the Asuka and Nara periods is, broadly speaking, continental art. Many of the artifacts may have actually been produced by the Koreans or Chinese, and only some by their Japanese apprentices (19), although others believe that the involvement of indigenous creators was greater.

Heian (794–1185):

• Contacts with China cease. Uncritical imitation of Chinese patterns is weakening. Typical Japanese creativity is developing.

• The most decorated objects include tebako and suzuribako boxes, mirrors, furniture, screens, litters, musical instruments and many everyday products, such as fans, sword sheaths, saddles, lanterns, dishes, etc. • Fabric and fittings reinforcements are introduced at the edges and joints.

• Gilding applied with a brush was replaced by the flourishing technique of "spraying" (maquette) with various gradations of metals, mainly gold. The application of gold foil continued in sheets or in a modified manner in the form of small geometric pieces.

• The togidashi technique is being developed, where decorations are covered with a layer of lacquer, which is then sanded off, and an image and background appear on one surface. The foundation technique also appears - covering the entire surface uniformly with a metal coating (powders or flakes).

• A new aesthetics of decoration is created. Instead of symmetry, asymmetry and poetic compositions appear, natural, mythological elements and empty spaces dominate, as well as representations of fragments and cuttings instead of the whole theme.

• High demand from the imperial court and temples causes an increase in the production of lacquer used to decorate furniture. Artistically, the motifs are directed towards the sublime tastes of the aristocracy. "The focus was on refined simplicity, asymmetry, free surfaces, fragmentation and suggestion," which brought lacquer decorations closer to painting (6).

• The typical Chinese depictions of stylized and expressionless figures are slowly being replaced by a more free approach, expressing rhythm and movement and individual facial expression.

Kamakura (1185–1333):

• The samurai era is reflected in art. Military themes appear. The court culture of the Heian period gave way to the warrior culture. Subtlety is replaced by simple motifs and rich gold decorations. New hiramakie (low relief) and takamakie (high relief) techniques were widely used. A new mass was introduced for the sabi priming layers (pumice, water and lacquer). The nashi ji technique (Japanese pear peel) is created. Kamakura-bori is also used - a technique similar to the Chinese tsuishu method. The motifs are more realistic, stronger in appearance, sharper, more detailed, although nature still dominates. The influence of Zen Buddhism is visible.

• Orders from temples and the court are increased by patronage from the shogunate.

Muromachi (Ashikaga) (1336–1573):

• The period of flowering of visual arts. There are landscapes inspired by Chinese ink painting. The lacquer carving techniques of kamakura bori (painting alternately with black and red lacquer, which after rubbing gave a three-dimensional effect) and chinkin (scratching, engraving and filling with lacquer) were developed.

• Items that are eagerly decorated include utensils for chadō (tea ceremony) and odor recognition (kōdō), as well as painting/writing utensils.

• The works are simpler and more artistic, which changes at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries. The years 1467–1573 were the period of sengoku jidai - permanent civil war. Some changes in composition occur during this period. Instead of subtlety, airiness and intellectual experiences, more realistic, monumental and expressive, sensual images appear.

Julia Hall Bartholomew, in a 1912 article, writes: “Until the 10th century the design was simple, but about this time it became more complicated. The nobility began to use articles decorated with gold lacquer. In the 12th century, almost every object was lacquered with gold, even carriages. At that time, the painter and the artist were separate entities: the former made an object and gave it a beautiful surface, and the artist painted the decoration. There was some minor progress between the 12th and 15th centuries, but this was unremarkable until the beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate around 1600 CE. Then art developed widely; there was a chance for aesthetic satisfaction, and the sense of beauty began to influence the overall situation. In those days, when daimyō encouraged arts and crafts, selected works were produced for their use, requiring unlimited time and the utmost care. The painter and the artist then united as one, which resulted in the creation of works of the highest technical and artistic value. The worker was clothed, housed, and fed by the daimyō he served. Having thus satisfied his needs, and gaining recognition for the quality rather than the quantity of his products, he performed his work with great skill and patience, his sole object being to produce articles of the highest beauty and perfection and to please his feudal lord.” (27)

Momoyama (1573-1615)

• The art of lacquerware, like other arts, developed under shoguns. There is a growing interest in decorating personal items, including an important element of new fashion - inrō.

• Among the techniques, makie, nashiji, chinkin bori are preferred, more shades and colors are used. Various methods are combined to obtain the most optimal results. The lacquer is of extremely high quality.

• The decorations are mainly devoted to the motifs of flowers and other autumn plants (often chrysanthemums and paulownias). • Mon family coats of arms and symbols of strength - eagles and oxen - are placed on the products. The motif of wheels immersed in water or sand is characteristic.

• The composition based on diagonals predominates, where the decoration begins in the corner and sometimes asymmetrically "flows" beyond the edges of the object, moving onto subsequent surfaces.

• For the first time, namban, i.e. European elements, appear among the motifs (in connection with the first contacts of the Japanese with Portuguese and Dutch sailors).

Edo (Tokugawa) (1603–1868):

• Edo (Tokugawa) was a long period of peace and isolation in Japan, which influenced social changes resulting in the development of the middle class. A large market for lacquerware is emerging. Expensive and beautiful lacquerware is a valuable gift and shows the status of the owner. The townspeople, unable to own weapons and other privileges, such as residences, realized their ambitions by purchasing works of art.

• The Edo period was the peak of technical and stylistic achievements in lacquerware. Technical perfection and mastery of copying masters.

• Tendency to present naturalism and scenes from everyday life. For example, instead of idealistic, nameless landscapes, specific views from actually existing places were presented.

• Bon trays and jubako food containers join lacquered objects, and inrō is growing in popularity. • Various techniques are combined, and in one object you can find both togidashi, takamaki and hiramaki, pearlstone inlays and elements made of metals other than gold and silver (lead, tin). All kinds of raw materials are used: wood, bamboo, eggshells, grains, string, plants, ivory, ceramics, glass, malachite, coral and new dyes.

• The composition is dominated by abstract elements, impressionistic effects, and the treatment of the surface as a whole. However, the decorative motifs are eclectic - next to lightness, elegance, master craftsmanship and inspiration from painting, there is the splendor of ornamentation and the exaltation of form over substance.

• The era of lacquer masters. There are lacquer art schools, such as Kōami, Koma, Kajikawa, Soetsu, and unique artists, such as Shibata Zenshin, Ogata Korin, Hon'ami Koetsu, Ritsuo (Ogawa Haritsu), Masanari, Doho and others.

Meiji (1868–1912):

• The decline of workshops as a result of changing the way of dressing to European ones; inrō becomes unnecessary. Fascination with the West results in disregard for tradition. Modern materials are slowly eliminating the use of lacquer as a material protecting against damage.

• Export to Europe is a salvation for lacquer artists, but the products lose their quality and artistic dimension. Compilations and copies dominate. The lacquer aesthetic based on makeup is often replaced with richer colors.

• Instead of a wide audience, interest in lacquerware is shifting to a much smaller number of collectors and people looking for oriental products. Objects covered with good quality lacquer are expensive because they require a lot of work and time, so individual works of lacquer, in particular, are no longer sought after in the face of competition from much cheaper substances and technologies that perform similar functions.

There are interesting observations in the interview conducted by Sawaji Osamu with Hidaka Kaori, professor at the National Museum of Japanese History in Sakura (Chiba) near Tokyo (VII), excerpts from which are below:

“(SO) Varnish has been deeply connected with the culture and life of the Japanese people since ancient times. (…) (HK) Anyway, the reason varnish spread throughout Japan was because it was extremely useful. For example, applying varnish to the container prevents water from leaking and increases its durability. It makes the object beautiful even after painting. It was also used as glue to join broken pieces of pottery. (SO) Lacquering techniques were refined from the Heian period (late 8th to late 12th century), when court culture flourished in Japan. What kinds of techniques have been developed? (HK) The most famous technique is maki-e. In this decorative technique, a brush is used to draw patterns in varnish on the surface of lacquered products. Gold or silver powder is then sprinkled and stuck to the varnish before the varnish dries. The origin of maki-e is unknown, but we know that maki-e lacquerware began to be produced in Japan in the 8th century. Maki-e experienced great development during the Heian period, when aristocratic culture flourished. Lacquer, gold and silver were extremely valuable, and maki-e was very expensive. (…) Maki-e was an important method of expressing the aristocratic sense of beauty. During the same period, lacquered wares were produced in other parts of East Asia, but maki-e was not used at all. For this reason, from the 10th century, maki-e was exported to other Asian countries as a Japanese specialty and became quite popular. (SO) How did lacquerware later spread to the general public in Japan? (HK) Because lacquerware used by the aristocracy had many overlapping layers of lacquer, it required a lot of lacquer and was extremely expensive. However, around the 11th century, a method was developed to produce finished lacquered products using one or two layers of lacquer over an initial rough coating painted on the wood grain using a mixture of powdered charcoal and persimmon tannins (...) During the Edo period, when the Tokugawa shogunate ruled Japan for about 260 years , starting in the early 17th century, the variety of lacquered products increased dramatically as craft techniques developed. For example, helmets, armor and other weapons, horse equipment and furniture. But for most people, lacquered products were expensive. When ceremonies such as weddings and funerals took place, large groups of people gathered for meals, so the use of many pieces of lacquered tableware became necessary. However, preparing all this lacquered tableware was not easy for one family. For this reason, it was common practice to borrow tableware from other families or share it in the community. (…) Personally, I use bowls and other varnished items and they have many uses. For example, lacquer does not transfer heat well and is not hot to the touch even with very warm drinks, so they do not cool down quickly. Extremely light, it feels soft when you hold it in your hands or put it to your lips.”

-

Types of lacquer

Currently, research indicates that the main ingredient of lacquer juice is urushiol, which is 60-75%, the rest is water approx. 25%, albumen 2%, a gum similar to gum arabic 4%, and small amounts of the laccase enzyme (1). Japanese chemists carried out research on lacquer at the end of the 19th century. It was found that lacquer has a sweetish odor, an irritating taste, burns with a bright flame, and emits thick black smoke. It looks like a greyish, thick goo. When left in the air, it produces a 'skin' that protects the remaining contents" (IV).

For hundreds of years, through various experiences, in Japan, lacquer producers, together with craftsmen and artists who use it, have used, invented, and improved various types of this material. Lacquer naturally varies depending on many factors. The differences relate to the region and place where the trees grow, the season, the age of the trees, what time of year the sap is collected, and what parts of the tree it was obtained from. Further differences are related to the processing technology and admixtures used.

Generally, types of lacquer differ depending on their composition and method of use. Simply put, they are divided into raw lacquer with or without various additives, and colored lacquer obtained by adding pigments and other ingredients (mainly black, red, and yellowish). In terms of its use, the lacquer can be used for priming, applying intermediate layers, and for finishing layers with or without polishing.

There are also types of lacquer for special purposes, such as gluing or dusting. There are a dozen or so types that are best known.

Crude lacquer

Ki urushi – raw lac, from the trunk of a living tree, harvested in summer and autumn. The autumn harvest has the highest quality and the lowest water content. Used in its natural form and with the addition of various substances.

Seshime – lacquer made of branches. It is considered to be of lower quality than ki urushi, but it is extremely hard once cured, although it hardens for a very long time (up to 20 days). Mainly used for priming. It is harder than ki-urushi, hence it was also used to paint scabbards for swords, shields, etc.

Nakanuri urushi – fresh lacquer, dehydrated, used for medium layers.

Transparent lacquer

Kijiro urushi – pure lacquer, without oil, transparent with an admixture of 1% gamboge (sap of the Indian Garcinia tree). Used in combination with dyes or for transparent coatings.

Kijomi urushi – filtered raw lacquer with 25% water content. Hardens better and faster. The best grade of ki-urushi, often mixed with black dyes. Syuai urushi – unrefined juice, with oil.

Shunkei urushi – transparent lacquer with 20% oil and resin. Used for top layers.

Hakushita urushi – transparent lacquer used as an adhesive for metal foils.

Shuai urushi – lacquer rich in oil, shiny when applied, used for mixing with dyes. The light amber, near transparent shuai is used as an intermediary to achieve other colors (except black).

Colored lacquer

Natural lacquer turns brown and dark in contact with air. Because of this, the color palette used to be very limited. Practically until the 18th century, only substances causing red and black colors when mixed with lacquer were in use. Later, natural dyes were used to obtain five colors: black, red, blue, green and yellow. It was only in the 19th century that new and later synthetic dyes were introduced, making it possible to obtain other colors and shades. Various components were used to color the lacquer. Natural cinnabar (mercury sulphide), iron oxide-rust (benigara) and plant components (egoma, gardenia) were used for red lacquer. To obtain the black color, the admixtures contained tar (soot) from burning pine resin or prepared iron filings. For other colors (yellow, green, brown), pigments made of arsenic sulfide, indigo and cinnabar were used.

Ro urushi (kuro) - black lacquer obtained by mixing ki-urushi orkiiro (better quality) with iron filings boiled in rice vinegar. The surface layers are mirror-shiny after polishing. Over time, it turns slightly brown and matt. It comes in the varieties kuro nakanuri urushi (without oil), kuro nuritate urushi (with added oil), kuro roiro urushi (translucent, similar tokiiro, but dyed black). Black lacquer also comes in the form of a mixture with soot produced from burnt pine or from the process of burning candles instead of iron filings.

Shu urushi – raw or transparent lacquer with the addition of oil and dyed red. After application, it does not require sanding or polishing.

Nashiji urushi - transparent, known as "Japanese pear skin". Obtained from older trees, high-quality lacquer is mixed with gamboge (sap from the Indian Garcinia tree, giving the lacquer a yellowish tint). Mainly used to cover small pieces of gold and other metals when finishing the interior of a product or for artistic purposes.

Other kinds of lacquer

Nuritate urushi – raw lacquer with the addition of turpentine and to-mizu (water with bits of stone after grinding the sword). Used for top layers of lower quality, cheap lacquer, left without sanding and polishing.

Jo-hana urushi – similar to nuritate, but with the addition of sesame oil, used for more common products, left without grinding or polishing.

Rose urushi – a mixture of kuro and kijomi or seshime, used to strengthen metal powders.

Mixtures used in varnish application procedures

Because lacquer was always quite an expensive raw material, and because it had to be applied thinly, various types of mixtures such as today's putties were used for thicker priming, filling gaps and bottom layers. They usually consisted of inferior (cheaper) grades of lacquer and materials such as plant fibers and clay.

Kokuso - shreds of hemp or jute fabric mixed with rice starch and seshime lacquer to create a thick paste.

Jinoko – powdered burnt clay and seshime lacquer in a 1:2 ratio, other proportions are also used, and the addition of rice starch.

Tonoko – similar to Jinoko using a different, delicate clay of various gradations (Mount Mari). Kiriko – a mixture of jinoko and tonoko plus seshime.

Sabi - 2 parts tonoko clay and 1.5 parts seshime with 1 part water.

Mugi-urushi – "wheat lacquer", a mixture of seshime lacquer and flour. Used for fabrics reinforcing wooden joints.

Nori urushi – rice and ki urushi paste in a 1:1 ratio used for an application protecting paper or fabric.

Currently, stores in Japan sell lacquer in tubes and, for example, in the Watanabe Shoten store in Tokyo you can find the following types of lacquer: seshime,kiiro, roiro, syuai, kuro nuritate, kuro nakanuri,kiomi and colored lacquer. Prices vary depending on the origin of the lacquer (from Japan or China) and its quality and range from 1,500 to 8,000 yen for a small 40 gram tube (approx. from PLN 40 to PLN 220) (VIII). In addition, you also need to add transport costs and customs duties. Lacquer can also be purchased in online stores in Europe, but the selection is smaller and the prices are much higher.

Technology of applying japanese lacquer

For 2,000 years, until its almost complete decline at the end of the 19th century, Japanese lacquer developed dynamically, but rather under the influence of various artistic trends, because technologically, most of the rules and procedures had been developed a long time ago. The material that is to be covered with varnish without additional decoration or before any decoration must be properly prepared. Apart from specific lacquer techniques that do not require the creation of "background" coatings, in most cases such a background is created as a result of a multi-stage technology. In the case of, for example, vessels such as bowls, plates, etc., the final effect is this background, i.e. a uniform, specially prepared lacquer surface. As mentioned above, the varnish does not "dry" through oxidation reactions in contact with air or similar processes that take place when using paints etc. media. The "drying" (hardening) process involves polymerization using enzymes in contact with air with a humidity of 85% and a temperature of approximately 20 degrees Celsius. To achieve this, varnished objects are placed in special boxes or wardrobes called muro, which used to be sprayed with water or lined with wet rags, and the work was carried out during periods when the temperature was appropriate. Currently, electrically heated cabinets equipped with devices ensuring appropriate humidity (even with automatic control) are used. The hardening time depends on the substance with which the object is currently covered. In the case of thin layers of lacquer, 8-10 hours is enough, in the case of thick layers, e.g. kokuso or jinoko, this time is significantly extended to several days or even weeks.

The procedures for applying varnish are generally divided into three parts:

Shitaji nuri (priming layers)

Naka nuri (mid layers)

Uwa nuri (top layers)

In the book "Urushi no waza", the authors include a list of activities necessary to apply varnish, covering approximately 20 stages (1). These include, without taking into account the product being sent for drying (curing):

1.kiji - preparation of the substrate, e.g. wood

2.suikomidome – priming the substrate with a layer of ki urushi

3.karatogi – dry sanding with sandpaper (in the old days, thistle was used, which has crystals in the stems)

4.nunobari – covering the surface with a damp fabric by gluing it with nori urushi This step is in many cases omitted if reinforcement of the substrate is not required, or performed only in parts of the product (joints, edges, etc.)

5.karatogi – dry sanding with sandpaper

6.jitsuke – rough primer by applying jinoko with a spatula

7.karatogi – grinding with rough stones (toishi)

8.kirikotsuke - middle ground, applying jinoko mixed with tonoko, water and ki urushi with a spatula

9.karatogi – grinding with rough stones

10. sabitsuke – the highest priming layer of tonoko with water and ki urushi applied with a spatula

11. sabitogi – grinding with stones of higher gradation

12. sabitsuke – another priming layer applied with a spatula

13. sabitogi – grinding with stones of higher gradation

14.suikomidome – application of ki urushi painted with a brush

15.sumitogi – wet grinding with charcoal

16.shitanuri – first layer of black lacquer (naka nuri urushi) painted with a brush

17.shitanuri togi - wet grinding with charcoal

18.nakanuri - second layer of black lacquer (naka nuri urushi) painted with a brush

19.nakanuri togi - wet grinding with charcoal

20.uwanuri - third layer of black lacquer (naka nuri urushi) using roiro urushi (of the highest possible quality) painted with a brush

21.uwanuri togi - wet grinding with charcoal

22.roiro sumi togi – grinding using the so-called "crystal" (formerly using special charcoal from magnolia, camelia and paulownia - roiro sumi)

23.doozuri – grinding with tonoko mixed with oil (in the past, powdered burnt deer horn was used)

24.roiro migaki – final polishing using 6 additional steps

24a. application of a thin layer of kijomi urushi

24b. polishing with polishing paste

24c. application of a thin layer of kijomi urushi

24.d polishing with polishing paste

24.e application of a thin layer of urushi (sometimes additionally wiping the applied urushi with paper is added, leaving an extremely thin lacquer film)

24f. final polishing with paste on the leather (formerly with a fingertip)

The above-mentioned technology results in obtaining black lacquer polished "to a mirror", without flaws on all surfaces and elements of the workpiece.

Of course, techniques are also used to obtain a matte varnish that simulates other materials such as metal, stone or uses the texture of the substrate (fabric, braid, rope, raw wood, etc.). These cases are described in a separate article titled "Techniques and Motives".

Raymond Bushell provides a list of several dozen stages of work using lacquer as part of the description of creating an inro. These include, among others, activities related to the preparation of an appropriate object made of paper, wood or other material, priming, grinding, polishing, applying intermediate and finishing layers, and then approximately 20 stages of decorating in the maquette technique (20). Bushell also presents the next steps appropriate for preparing techniques that use mother of pearl (aogai snail shell) - raden.

Below is the appearance of the subsequent layers (based on information contained in "Japanese lacquer Nambokucho to Zenshin")

1. persimmon/ki urushi application 2. kokuso application 3. fabric application 4 and 5. jinoko application 6. tonoko application 7,8,9,10. application of tonoko with increasingly smaller gradations, between applications wet grinding with stone and carbon 11. final layer of primer after application of ki urushi mixed with carbon 12. application of black varnish 13. wet grinding with stone 14,15,16,17,18,19, 20.21 alternating the application of increasingly better quality black lacquer with grinding with magnolia charcoal 22. polishing with powdered deer antler

Various sources also mention other traditional names of procedures used to apply varnish. Below is a list of several of them in alphabetical order.

Dōzuri (polishing method) It involves polishing the varnished surface with a mixture of tonoko powder and rapeseed oil using a piece of cloth. Kawari nuri (special decoration techniques) Applying varnish with various decorating techniques. These may include techniques using maki-e, egg shells, metal foil, plants, seeds, etc.

Kijiro-nuri (transparent lacquer) Transparent varnish is used to cover the upper layer. It is often used directly on the surface (e.g. wood) to highlight the grain pattern or texture.1.

Kyūshitsu (applying urushi, varnishing)

Kirikotsuke (medium primer coats) Applying kiriko (lacquer, water and tonoko with jinoko) with a spatula

Kyūshitsu (general name for layering lacquer) It involves repeatedly applying the bottom (shitanuri), middle (nakanuri) and top (uwanuri) layers of lacquer with a spatula and sanding them. Depending on the method, the top layer is polished (roiro shage) or left unchanged (nuritate).

Kokuso shitaji (filling) Applying the bottom priming layer with a spatula and covering any wood defects/blemishes. Kokuso is made from lacquer mixed with rice paste, wood sawdust or fabric fibers.

Kuro urushi nuri (black lacquer) A method of applying the top layer of black lacquer with a brush. Kuro urushi (black lacquer) made with iron filings is suitable for polishing. Another type with the addition of soot remains unpolished in a more or less matte form.

Mugi urushi (urushi mixed with flour paste) Applying mugi urushi (paste made of flour, lacquer and water) with a spatula. In addition to nunokise, it is also used for gluing shells, mats and other materials.

Nori urushi (urushi mixed with rice glue) A mixture of glue and varnish. Rice glue is made from cooked rice flour. Used interchangeably with mugi urushi.

Nunokise (fabric pasting) Nunokise involves gluing pieces of cloth onto a wooden substrate using mugi urushi (lacquer mixed with flour paste) to strengthen the joints and minimize wood shrinkage. The fabric is more often glued in places sensitive to damage, less often on the entire surface.

Nuritate (unpolished finish) Finishing procedure by painting without polishing, uniform surface without leaving brush marks and dust particles.

Roiro shiage (finishing - roiro) A procedure of alternating polishing with charcoal and applying very thin layers of ki urushi (black lacquer or transparent). Finally, it is polished with a very fine polishing material mixed with oil. resulting in varnishing.

Sabiji, sabitsuke (further priming) Applying a layer of sabi (fine tonoko powder, water and raw lacquer) with a spatula.

Shibo urushi (lacquer mixed with sticky materials) Applying lacquer mixed with various materials such as tōfu, egg white, gelatin, powdered or cooked flour, etc.

Shitaji (priming) Applying priming layers based on gluing fabric, using layers of kokuso, jinoko and tonoko as well as raw lacquer, using mixtures with gradually smaller gradations. There are kataji (strong foundation) techniques such as honji (clay with raw lacquer), honkataji (foundation with lacquer, clay and water), kirikoji (foundation with lacquer, water, jinoko and tonoko).

Shu urushi nuri (red lacquer) Covering the upper layers with a brush with red varnish. There are several varieties of such varnish (with different shades).

Suri urushi (coating finishing) Painting a thin top layer of lacquer with a brush and then wiping it off with paper. Also used to strengthen metal particles in the maki-e technique.

Tsuyaage (final polishing "to the mirror") After repeated dozuri, further polishing involves using tsunoko (powder from burnt deer horn or other extremely fine material mixed with oil) using the fingertip or palm of the hand.

The substrate on which the varnish is applied must be perfectly prepared. Irregularities and defects make filling difficult. Applying individual layers requires a lot of experience, especially with intermediate and final layers. Lacquer applied too thickly hardens on the surface faster, resulting in blemishes (the so-called orange peel) and the drying time is very long. If applied unevenly, it dries unevenly, causing problems with sanding, not to mention material loss. Lacquer applied too thinly (except for the roiro migaki process) does not provide sufficient coverage and requires increasing the number of layers.

The environmental conditions at the naka and uwa nuri stages are very important. Cleanliness and lack of dust are crucial, because even the smallest dirt stuck to the surface of the varnish is impossible to remove without sanding the entire layer.

Alviso B. Stevens lists his observations about the work of painters a hundred years ago(4). In principle, they do not differ from the principles used today and throughout the history of lacquer in terms of the method of execution, environmental conditions and final results. This proves the extraordinary preservation of tradition on the one hand and the craft technology, which cannot be automated in any way, on the other.

Different sources and stories give different numbers regarding the number of layers of lacquer that would be used - from a dozen to several hundred! However, a typical varnish coating does not contain more than necessary layers: several priming layers and a few finishing layers. The exception here are carved lacquer techniques, e.g. tsuishu, where the technology involves creating a very thick coating (up to about 1 cm) from many overlapping layers and then cutting out appropriate patterns in such material.

From a technical and functional point of view, Japanese lacquer is today successfully replaced by various types of varnishes and synthetic coatings as well as plastic products that match its durability, gloss, perfect surface and flexibility of coloring and application possibilities. However, a trained eye will notice its exceptionally shiny surface, and for now, it would be very difficult to achieve artistic effects in decoration without the use of traditional craft technology. A comparison between painting and computer graphics comes to mind here.

At: 【うるし濾しの音】漆漉し 漆 伝統工芸 白根仏壇 塗師 新潟 職人 ASMR 作業音 japanese craftsman (youtube.com) you can see the processes of preparing and filtering of lacquer.

At: Kyo-Urushi in the Making - How it's made - Japanese Traditional Art (youtube.com) you can see the process of lacquer application.

Thank you very much for reading, I would be extremely grateful for any comments. Contact: use the form on the website in the "Contact" tab or directly to piotr@faryna.eu. I will refer to each of them in the articles in the "Notes and observations" section - article number "0".

Facebook https://www.facebook.com/piotr.faryna

However I do not intend to collect, process or share personal data in connection with running this website, but if something like this happened, I hereby declare that: the personal data administrator is Piotr Faryna. Your data may be made available/transferred only in the cases indicated in the regulations at the request of authorized institutions. You have the right to request to view, change or delete your data.

Kontakt

Menu

Mój profil

Strona www stworzona w kreatorze WebWave.